|

Earlier this month I spent a weekend at Camp Berea on Newfound Lake in New Hampshire, the site of the retreat I wrote about back in September. This time, I attended with my daughter for the camp’s annual Mother/Daughter Retreat. There was a lot of anticipation around this event for both of us. My daughter had been looking forward to it ever since our first trip to the camp last summer with families from our church, Highrock. After making many arrangements -- packing, renting a car, organizing supplies and directions for the events my husband and sons would attend at home in our absence -- my daughter and I climbed into our little rental and headed north. The theme of this year’s retreat was Brave. And it was courage (and stamina) I felt I needed in big and little doses and we battled traffic and unfamiliar roads in order to get there, faced uneasy curiosity about whom we would be sharing a cabin with and agonized over the burden of activity choices as we decided (and revised) how to spend our limited time, all while emotions ran high (and, at times, low) and fatigue snuck up on us like a side tackle. I tried to step up to the plate as often as I could. (Sporting analogies abound in this one; get ready.) I hate games. But I pulled a muscle going all out in a version of capture the flag in the gym. (During the round of mothers versus daughter, the mothers won. I felt I had played my part.) When my daughter wanted to climb rocks out on the shoreline I gritted my teeth and joined her (figuring if we fell in, at least we could swim). Later, I swiftly removed the tick crawling down her arm. When she wanted to check out a single kayak from the boathouse I said a prayer asking for protection before requesting two boats which we lugged awkwardly down to the tiny beach. She had never gone out on her own before, and I still approached kayaking with trepidation and slight claustrophobia from being so low and straight-legged in the boat. But she did great -- and I navigated my role of giving her space while making sure she didn’t get trapped in a tight spot against the current either. It turned out my daughter wasn’t the only brave girl there. We waited in line for two hours for her to have a chance at the high ropes course...only to be told they were cutting off the line, claiming they were out of time and had to pack up the equipment so everyone could get to dinner. In a compassionate response to my daughter’s audible regrets, a girl in front of us turned and offered up her spot which my daughter accepted gratefully. And then I watched, my emotions a confused mix of relief and nervousness, as she hoisted her harness first up a rope ladder tunnel and then over the challenges high in the trees before taking that death-defying step off the final platform, hoping with every fiber of my being that the tension rope attached to her harness would do its job and auto-repel her safely to the forest floor. I had promised her everything would be fine. That rope needed to come through for me. (Spoiler alert: it did.) We noticed that there was another mother-daughter pair in attendance who we know from our church. When I commented how pleasantly surprised I was to see some familiar faces, my daughter asked something like, “Wait, isn’t this a Highrock camp?” It’s funny what you feel you need to explain to your children (“Don’t touch that, you’ll get dirty!”) and what you inadvertently assume they understand. Because our church had rented out the camp last summer when we were first there, my daughter had assumed this camp was run by Highrock. I explained that Camp Berea is a Christian camp, run by other people who want to teach about God and Jesus. When she commented that she thought her school teacher would like the activities offered I pointed out that I didn’t think he went to church but that we should ask him. I also felt like explaining that there were many kinds of outdoor camps with similar activities and that some of them didn’t also teach about God. But aside from spending quality time together and participating in these thrilling activity options, we were there to learn about God and Jesus. So I dragged her away from her favorite spot on the rocks jutting out into the lake in order to attend each of the four worship and teaching sessions scheduled throughout the weekend. I didn’t make her go to morning devotions. I didn’t think we were ready for such an in depth study (yet), but main speaker Erica Renaud did a beautiful and age-appropriate job of illustrating the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt and how it and other Bible passages depict people bravely following God. She challenged us to consider what it means to bravely follow God in our own lives, offering these guidelines: First, in order to say yes to moving forward with God’s call, we have to leave behind what was before (just as Moses left his life in Midian in order to obey). She asked what we would have to leave behind. Comfort? Expectations? Worries? Second, living bravely means we’re going to face challenges. When Moses first asked Pharaoh to release the Israelites, Pharaoh increased their work, effectively making life worse for God’s people. While Moses could have felt he had made a mistake by requesting his people’s freedom, he bravely (with Aaron’s help) stayed the course. Third, we overcome those challenges by fixing our eyes on Jesus. When Peter stepped out of the boat to walk to Jesus, he saw the wind and, taking his eyes off Jesus, started to sink. But, immediately Jesus reached out his hand and caught him. As Paul writes similarly to Timothy later, the message is this: Don’t get distracted (by what people say). Keep your eyes on Jesus. For even if we are faithless, he remains faithful. At the end of the third talk we had a chance to respond to her message. Erica invited us in groups to the front of the gym where we took turns painting a wooden cross with washable red tempera paint (a substitute for the lamb’s blood that the Israelites used to paint the doorframes of their houses to mark the passover). One by one we dipped the brushes into the paint and then ran the bristles over the wood in two directions. First, we painted down the main post as a confession of sin and that we too at times have looked away. Then, we painted across as a remembrance that Jesus is steady and has saved us. During the fourth and final session a few girls helped Erica act out the parable of the master who places three workers in charge of his money. The first two workers put the money to work and double their master’s money. The third, however, hides the money in the ground not wanting to lose it. Erica admonished each of us not to act like the third worker who says, effectively, “God, your word is too difficult for me to discern, so I’m just going to sit on it.” She returned to the Israelites at the moment of their escape when they were trapped between death by the Red Sea on one side and death by Pharaoh’s army on the other, a desperate hour when they cried out to God, Why? She points out that bravely following God requires risk because you’re not sure of the outcome. When we ask “why”, God answers with two reasons:

Moses set his eyes on God, told the Israelites to pack up and stretched his hands to invite God’s miracle of parting the Red Sea. If we aren’t brave then we won’t see the waters part. On the other hand, if we can be brave, then our obedience may lead to the deliverance of others. And God said, “I will be with you. And this will be the sign to you that it is I who have sent you: When you have brought the people out of Egypt, you will worship God on this mountain.” Exodus 3:12 But what do we do when the going gets rough? Perhaps we should remember Paul’s perspective in Romans 8:18: “I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us.” Recently some moms from church were asked what they wish they could have witnessed from the Bible. One mentioned the parting of the Red Sea. Wouldn’t that have been a terrifying and glorious walk to take between those walls of water? I doubt I’ll get to witness anything like that, but I am confident of the small glories I’ve seen thus far, a foretaste of heaven. At Camp Berea it meant getting in the boat, letting my daughter grow up a bit and taking the risk that she might not latch onto biblical teaching as readily as I hoped. “I don’t think my friends believe in God,” she told me. Being brave for me in that moment looked like being willing to look foolish in the eyes of the world as I stayed steady in my intent to keep God at the center of our household, believing him to be the good rope that lowers me safely when I step into the unknown. Where does my help come from? God commands in Deuteronomy 31:6: “Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid or terrified because of them, for the LORD your God goes with you; he will never leave you nor forsake you.” His message is straightforward...and just as true for us today: Go, I will certainly be with you! Hear Paul’s encouraging declaration: "Therefore I endure everything for the sake of the elect, that they too may obtain the salvation that is in Christ Jesus, with eternal glory." 2 Timothy 2:10 "For God did not give us a spirit of timidity, but a spirit of power, of love and of self-discipline." 2 Timothy 1:7 Go, I will certainly be with you! *N.B. All Bible passage references, as well as the phrase “Go, I will certainly be with you!” are taken from Erica Renaud’s talks.

0 Comments

During my medical training, doctors around me referenced Samuel Shem’s The House of God as the classic story of young doctor’s experience in an American hospital. I can’t recall anyone sharing particular details from the text. It was mentioned more in passing, with raised eyebrows, the look of an inside joke, the kind of look I never asked to be explained for fear that my ignorance would be laughed at. At that point I had already dabbled in writing about my experiences in medicine, starting with the anatomy lab. I decided I needed a copy of Shem’s book. I needed to know what the precedent was, what I was up against in trying to enter this particular niche in the literary field.

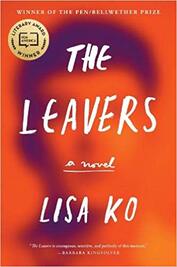

History is a little blurry at this point, but I think my husband’s grandmother gave me the book for my birthday while I was an intern at a Boston-area hospital. I held the thick yellow paperback, felt its weight and gave it a spot on the shelf where I could gaze at it in reverence. I didn’t have time to read it right then. A couple of years passed. I left medicine, but I continued to write. Now I was working on a piece about one call night from my internship. The entire manuscript was about one night. I wanted to convey how long those nights felt, how much could happen, how the events could change you. I thought about reading The House of God at that point, for research purposes, to see how it was told in a way that was embraced so widely, in a way that sold so well. In the end, I left it on the shelf. I didn’t want to be influenced by someone else’s style. I wanted to tell my story and know it was purely my own. I finished my piece and passed it around to friends. Their overall question after reading it was: why was this doctor so upset? The protagonist of my story looks on her job with dread and cynicism, and it’s almost funny how I assumed the reader would understand why. I wrote about shocking events, episodes that I hoped would communicate to the reader the strenuousness and at times near absurdity of practicing medicine. I wasn’t sure how to edit my work to bridge the gap between my story and the reader’s understanding. I let it rest. More than several years passed. This year I started a new piece, a memoir about becoming a family of six. Medical writing was, for the moment, something of the past. Sure, I have two and a half manuscripts that I would like to revisit someday, but I have other words in me I need to work out first. At the same time, this year has provided space to work on projects I’ve been putting off -- cleaning out the basement, organizing photos, finishing quilts...and reading those books on the shelf that for years I only stared at. I decided to crack open The House of God. It was time. There were years of mental distance between me and medicine, even between me and my writing about medicine. I could read it more objectively now and not worry about how it may affect my writing style. Right away I could see parallels between our tales. Shem’s protagonist Roy Basch is nearly nauseated by the fear and anxiety he feels when he thinks of starting his internship. (I could relate.) He grows angry and cynical and depressed with each shocking and strenuous patient encounter. (I could relate.) When patients die, he and his fellow residents aren’t provided with a supportive environment to debrief events and grieve. (I could relate.) Stylistically, I found myself in my own readers’ shoes as I criticized the story. Why was he so afraid to start the internship? What had happened before to give him the impression that it was something to fear? And as his mental health spirals downward, I wanted Shem to carry the reader into that with discrete examples explaining why, examples that I found were glossed over in order to focus on Basch’s reactions to them. I started to develop a checklist for what to look for when I went to revise my own work. But this doesn’t scratch the surface of my main objections to this book and why I absolutely cannot recommend it to you. If you have read this book and think it is an important work, will you please share your insights with me? Because while I tried to peer through the fog of distracting issues to discern what it was like to practice medicine at that point, I grew nauseated myself as I read of his sexual exploits with the nursing and house staff, the way he continually cheated on his girlfriend, the racist language, the sexist language and the fact that the only female doctor described was the most difficult, uncaring, repressed creature on the ward. Is this one of those books that you’re supposed to read “in context”? Hey, it was the 70s. Loose morals. Paternalistic medicine. White tights on nurses. Condescension for foreign or non-white doctors. Well I didn’t want to “read in context”. I wanted to burn my copy and thank God that medicine had changed. Perhaps it needs to continue to evolve -- after all, I was just as angry and cynical and depressed during my own internship, although my behavior was saint-like compared to Shem’s characters. I finished the book and knew I had work to do. I have stories to tell. I want my readers to understand why interns might feel that dread about going to work. I want them to understand why we might get angry and cynical and depressed. And I want to update this story with the times. My graduating class from medical school was greater than 50% women. Times have changed. In a recent afterward to his book, Stephen Bergman (Samuel Shem is a pen name) suggests that his intended audience was other interns. He felt good when other interns read his work and could laugh and cry along and not feel so alone. I could not get over my disgust of the language and certain events in order to relate to the characters as fellow interns, but reading his intentions made me want to reconsider my own intended audience. I wanted to make the experience of medical education accessible to those outside the field. I wanted people to sympathize with doctors in a day and age when paternalism has long faded and patients, being more informed than ever, demand near perfection from their providers. I have stories to tell, and, if I hold onto no other redeeming quality, Shem’s book inspired me to continue the work I started so many years ago.  I picked up a copy of this book to read for the book club at my local branch library. I had a hard time getting into it. I didn’t like the premise, for starters -- a selfish mom who seemingly abandons her son? And as I began to turn the pages I liked the characters even less. I didn’t identify with them at all. I didn’t agree with their decisions. And then, at a certain point embarrassingly deep into the novel, I realized I had gotten the story entirely wrong. Spoiler alert: If you think you might pick up this book, stop here. Read the book first. If you don’t have plans to pick it up, please read on. Lisa Ko’s The Leavers won the 2016 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction and was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction in 2017. The social issue that Ko presents is one that I would expect from sometime last century perhaps but not from our government today. Let me illustrate: Do you remember being scandalized (as I was) to learn about the Japanese Internment Camps in this country during WWII? The shock of all knowledge softens with time, or perhaps we just learn to cope with it, telling ourselves to read history in the context of its day and to appreciate how far we’ve come as a society. I have read a surprising number of books in which the mother abandons her children. I have heard some readers defend these mothers, but, for me, it never make sense. In The Language of Flowers, a teenage mom gives up her baby when she feels overwhelmed and without resources. In Homecoming, a mother of four has a mental breakdown from the stresses of single parenting. (Okay, I don’t have experience with single-parenting, but I empathize with the stress of having four children. In the end though, I wanted her to get treatment and get back to her family.) Now there’s Polly Guo in Lisa Ko’s The Leavers. Polly is a Chinese country girl who becomes pregnant after fleeing to the city to work towards a better life. Realizing she would be locked into a life she doesn’t want if she bears her child, she seeks an abortion -- a procedure she is denied because she isn’t officially a city resident. She flees to America in search of the freedom to pursue a life she wants. When she seeks abortion again in New York City she is told no doctor will abort a fetus seven months along. She goes on to bear a son, totes him to work with her and when he is about a year old, sends him back to China to live with her father until he is old enough to begin school in America. I did not identify with this woman at all. I judged her for being irresponsible and getting herself pregnant, observed her confess that after she twice tried to abort her child, she once tried to abandon him as a baby, leaving him beneath a park bench for several minutes before changing her mind and running back to retrieve him. Eleven years later when she says she wants to move to Florida, she is met with resistance by her son and her then boyfriend. The next day when she disappears, I assume she finally made the decision to abandon them both. Ko’s tale jumps between Polly’s perspective and that of her son -- another character who I also struggle to muster up any sympathy for. On the one hand, the reader can sort of understand that being abandoned as a child can really impact your life. On the other hand, the son makes a series of really awful decisions on his own. Still, it’s probably human nature that leads the reader to lean toward blame -- and in this case, it’s pretty easy to blame the absent mother. The chapters jump around in time as the son eventually finds his mother and continues to seek answers. Enter my embarrassment at not understanding the issues sooner and my disgust at realities brought to my attention. While reading Ko’s book, I didn’t understand until the end that the mother, Polly, was an illegal immigrant, that the debt she refers to frequently is the one she acquired from being smuggled into New York from China in a box. For some reason, I chose to believe that her entry was above board. But when I found out it wasn’t, I sympathized with her. She had no options in China, no room to grow. I watched her make one impossible decision after another - to bear her son, to send him back to China to live with her father until he was old enough to go to school, to bring him back to New York, to provide for him. Shame on me for figuring that when she disappears it’s because she abandoned her child and life in New York. Of course, she had been deported. I was outraged when I learned that before being deported she was held in a detention camp for fourteen months where she lived under despicable conditions and was provided no social support or way to contact her family. Less than a year after Polly disappears, her son is adopted by a white couple in a New York suburb. Ko’s story isn’t told chronologically, and as I tried to piece together who knew what when, I couldn’t understand why an adoption agency wouldn’t try to contact a mother before giving her son away. Ko’s fictional tale was inspired by a 2009 New York Times article about an illegal immigrant from China named Xiu Ping Jiang who was arrested in Florida and then held in a detention center for over a year before being granted asylum. Xiu Ping Jiang bore two children in China before undergoing forced sterilization for violating the one-child policy. She was smuggled into the US in search of political asylum. Ms. Jiang’s eight-year-old son was adopted in Canada after trying to enter the US. Unfortunately, in her research Ko found other stories like this which influenced her work. From Lisa Ko’s website: "After being profiled in the Times, Xiu Ping Jiang was released from prison and later received asylum. She was lucky. Nearly a quarter of the 316,000 immigrants deported from the US in 2014 were parents of children who were US citizens, and there are currently more than 15,000 children in foster care whose parents have been deported, or are being imprisoned indefinitely. The Leavers is my effort to go beyond the news articles, using real-life details as a template from which to build from, not adhere to. It’s what I call the story behind the story, and it’s really the story of one mother and her son, what brings them together and takes them apart." The separation of families in attempt to solve the problem of illegal immigration is one that too recently made our stomachs turn over. I had neighbors attending protests and sending money last year when hundreds of kids from migrant families were separated from their parents under Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy.

But I didn’t know that detention centers existed otherwise. In The Leavers, Polly’s detainment at Ardsleyville is based on the actual Willacy County Correctional Center at the edge of Raymondville City, Texas. The conditions were said to be as bad as those portrayed in Ko’s fictional story. I had no idea that on the day my youngest children were born in 2015, the center was destroyed after a riot and fire. I had no idea that as I was learning how to nurse twins, 2,800 inmates were relocated to other facilities. What do we do with the knowledge that these things are happening around us today? I do not gravitate towards politics, and I have no understanding of immigration law. For now, I will simply continue Ko’s mission: to bring this issue to light and to help educate. So many people around the world live in darkness, with daily challenges that threaten their lives and livelihoods. I want my country to be a beacon of hope and opportunity where they can thrive. But if they aren’t allowed here, then is there is something we can do to reunite them with their children instead of adopting those children away and assuming we can give them a better life? Pray with me...for wisdom...and humility. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|