|

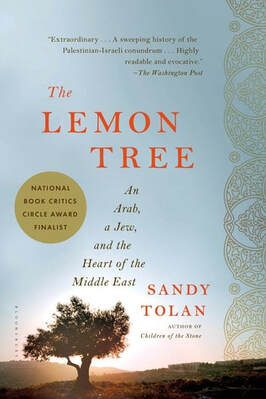

This book falls on a very long list of books I didn’t get around to reading when they were first popular. But Tolan’s story of crossing barriers to understand differences among us is far from a passing fad. It’s a little-practiced but desperately needed exercise in growing empathy that is relevant for any time. There will always be differences dividing the human race -- whether by race or culture or religion or politics or class or personality. And while diversity and inclusion groups have certainly made great strides to cultivate awareness and celebrate diversity, we need stories like Tolan to bring us beyond just saying it’s okay to be different. We need stories to teach us how to bring honor to someone who is different. It’s the simple but often-insurmountable difference between saying hello to your neighbor and inviting them over for a meal in your home.

Tolan’s narrative demonstrates that while Dalia and Bashir grow in their love for each other over decades of friendship, they retain a heartbreaking hesitancy to climb out of their entrenched ideals in order to pursue compromise. For the Palestinian, even as late as 2013 (in my edition of the book), 65 years after the 1948 war, no resolution is satisfactory besides removing any immigrant who arrived after 1948 and restoring the 1948 boundaries of Palestine, a change which would allow him to return to the home he was forced to flee that year. For the Israeli, the Palestinians must accept that the Jews need this land and must build new homes in Old Palestine, allowing her to retain rights over the Palestinian’s property which she inhabited when he fled.

Even with this stalemate, however, Tolan’s book is still worth reading. Perhaps in sharing their personal struggles, Tolan seeks to embolden others to join the conversation. In his words: “The key to...openness, [he continues] lies in the interweaving narratives: When someone sees his or her own history represented fairly, it opens up the mind and heart to the history of the Other…[in order to recognize] the humanity of the other side. ...I’m hopeful that the human story beneath this “intractable” problem will show that it may not be so intractable after all. As Dalia says, “Our enemy is the only partner we have.” (xix) What I appreciated most about this book was a chance to learn about the history of the region in a detailed way through a narrative structure, like that of the story of Bashir and Dalia. As I describe elsewhere in my blog this month in my review of Kendi’s in my review of Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning, I have always had a hard time remembering the dates and circumstances in a history lesson. One of my classmates this past summer shared an excerpt from her memoir about losing her connection to her Egyptian homeland since coming to the States. When she grounded Egyptian history in her personal memories, I was much more able to follow her experience, as I would have been otherwise floundering in a sea of names and dates, untethered to an hierarchy of importance in my mind. In trying to process Tolan’s feat of narrative nonfiction, I mulled over some pretty tough issues. First, I feel like I have to confess that I grew up believing in what I now feel is a myth of Israeli sovereignty. Second, I wonder if we might apply Gregory Boyd’s interpretation of Old Testament violence in this situation and consider that, while God definitely wanted his people in the Promised Land, he never wanted the Israelites to take it by force. While there are, for sure, religious reasons for Israelis and Muslims to lay claim to the land in question, I found it interesting that Tolan chooses to highlight families that are mainly secular. Still, there are, of course, strong religious implications. Israeli Operation “Wrath of God” in 1972, for example, reminds me of Boyd pointing out that the ancient cultures depicted in the Old Testament were proud of violent contests that demonstrated the power and victory of their gods. The Ancient Israelites were no different. They wanted to attribute the violent victories to Yahweh. And yet, Boyd suggests in his book that God wanted to give Canaan to the Israelites in a non-violent manner. As a Christian, it is important for me to study this. Christian backing for Israel is a strong part of American culture, and I want us to reconsider why. Christians have an opportunity here to replace the “an eye for an eye” thinking with Jesus’s admonishment to “turn the other cheek.” Regarding one such Christian, I have a vague memory of reading Blood Brothers by Palestinian-Arab-Christian-Israeli Archbishop Elias Chacour as a teenager. Originally published in 1984, I found the story eye-opening and moving. But for me, the conflict still felt very far away. Tolan’s narrative drives the matter home, for Americans in particular. For most of my life, the problem in the Middle East has been over there. And yet, here’s my third large takeaway: Many of the details found in this narrative eerily mirror those at home, making it painstakingly clear that the issues we see in the Middle East are not specific to the Middle East but perhaps examples of the broken condition of the human spirit. For example, are Americans not invaders in their land, pushing out the indigenous people, as the Palestinians accuse the Israelis? Are Americans not battling with the concept of reparations? Are Americans not locking up their own (watch 13th on Netflix for shocking statistics on mass incarceration) and disenfranchising large portions of the population, as Tolan included the estimate that 40% of the adult male Palestinian population had done some jail time in the 18 years follow the 1967 war? And are Americans not on display for the whole world to criticize? (I don’t offer a particular example for that last question, but I don’t expect you have to think too hard to come up with one.) Bashir points out a humbling difference between us when he says: “Palestinians are stones in a riverbed. We won’t be washed away. The Palestinians are not the Indians. It is the opposite: Our numbers are increasing.” (260) Those statements made me incredibly uncomfortable, as did these: “[Bashir] was skeptical that this longing for Zion had much to do with Israel’s creation. “Israel first came to the imagination of the Western occupying powers for two reasons,” he told Dalia. “And what are they?” she asked in reply, now feeling her own skepticism grow. “First, to get rid of you in Europe. Second, to rule the East through this government and to keep down the whole Arab world. And then the leaders started remembering the Torah and started to talk about the land of the milk and the honey, and the Promised Land.” “But there is good reason for this,” Dalia objected. “And the reason is to protect us from being persecuted in other countries....” “But you are saying that the whole world did this, Dalia. It is not true. The Nazis killed the Jews. And we hate them. But why should we pay for what they did? Our people welcomed the Jewish people during the Ottoman Empire…. “ Referring to the conflict Dalia and he both find themselves in now, drawn together by the yearning for the same home, Bashir continues: “Why did this happen, Dalia? The Zionism did this to you, not just to the Palestinians.” (161) Dalia’s husband admits at one point that Palestinians “have a legitimate grievance against [Israelis]...And deep down, even those who deny it know it. That makes us very uncomfortable and uneasy in dealing with you. Because our homes are your homes, you become a real threat.” (211) It takes decades for Dalia to even consider the possibility that Bashir might have a claim to her family’s home. Prior to meeting Bashir, she believed the story she was told throughout childhood, that the Palestinians fled their homes in 1948, too cowardly to fight, and that because of this they did not deserve the land. I found it really hard to understand her reasoning. Even if they hadn’t been driven out (as she later learns was the case), perhaps they weren’t fighters? Perhaps they were hoping for nonviolence? Why is it cowardly to walk away from a bully when he picks a fight? As Dalia searches for a way to make things right with her friend Bashir, she has an opportunity to foster dialogue between Israelis and Arabs and is “amazed at the outpouring of emotion from Arab citizens who began talking openly about their family stories from 1948. “Suddenly, Arabs opened up with statements of pain,” [Dalia’s husband] recalled. “Liberal, well-meaning Israelis who thought they were building cultural bridges and alliances were forced to confront the fact that there were endemic problems and injustices in Israeli society that required much more than cross-cultural encounter and coexistence activity. It required social and political transformation on a societal scale.” (240-1) To me, this sharing of stories is what we’re encouraging in America right now. The writing center where I take classes seeks diversity of writers, and as frustrated as I am that I continue to be waitlisted for classes, I can’t blame the organizers for prioritizing stories of the unheard over someone like me from middle white America. My book club has added more color to its line-up of authors, and I wonder how you might search for and absorb stories from writers that have long gone unprinted. Overall, in The Lemon Tree, while Tolan repeatedly drives home the love of the Jewish people for the Promised Land, I get a more sympathetic view of the Arabs. I wonder how Jewish Americans respond to this book. I wonder how it has been received in Israel. I don’t want my observations and comments to be read as a criticism of the Jewish people but rather an inquiry into the justifications of Israeli policy. As I’ve written elsewhere, none of my blog posts are comprehensive analyses of the issues they discuss. On this issue, if you have read material with a similar or opposing perspective, will you list it below so we can all continue to learn from each other’s stories? I want to leave you with a heart-warming perspective that has the potential to empower us all. Before Tolan gets into the quagmire of Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he takes the time to show us the goodness we often overlook due to the incredibly distracting force of war. Prior to this book, for example, I had no knowledge of the Bulgarian response to the Holocaust and how civilians banded together to protest the deportation of their Jews, saving 47,000 lives. To describe the intricate network of small responses that added up to this dramatic result, Tolan attributes the phrase “the fragility of goodness,” coined by Bulgarian-French intellectual Tzvetan Todorv, meaning “the intricate, delicate, unforeseeable weave of human action and historical events.” (43) What he means is this: your good deed is never wasted, no matter how small. We cannot see the trickle down effects of our actions, good or bad. We can only choose the next right thing.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|