|

I read 59 books in 2019. And yet, I was intimidated when my friend asked me to read the Bible with her this year. Sure, there are 66 books in the Protestant Bible, but some of those are less than a page long. What’s the big deal? Okay, obviously, overall, the Bible is a large, dense book. I can remember other times in my life when I vowed to read the Bible cover to cover, only to stop a few months in. I was even hesitant to write this post this month and confess to all of you readers that I have this goal! Somehow I know that the risk of not reaching the end is a number far greater than zero, and far greater than I would like to admit. And it’s hard to start at the beginning. The writing style of the Old Testament can be incredibly dry...especially if you don’t also take the time to interact with the text and ask what it means, not just glaze over the very long lists of genealogies and laws. Then again, if you take the time to interact with the text, you might become dragged down by difficult material...and seeming contradictions.

No surprise there, perhaps, but we have held ourselves accountable to checking in with each other regularly. Every Monday I can expect a text from my friend with a reaction or question about the reading, and I respond in kind. She has been great about referencing outside articles and hunting down answers, perhaps to the detriment to our page goals, but perhaps to the enrichment of our experience.

If you study the Bible even casually, you will likely wonder how the Protestant canon was chosen, and how the order of the books was decided. In the introduction to the Chronological Study Bible, the contributors note that the canonical order was determined by the Latin version translated by Saint Jerome in the 4th century A.D. In this study Bible, the contributors arranged the texts according to narrative structure, grouping texts not according to when they were written but by common time periods and events, so we can appreciate how God’s story unfolded over time. The contributors caution readers that rearranging the text into chronological order “will probably highlight some difficulties that many Bible readers have never noticed. The Bible as it really is, not as we have imaginatively harmonized it in our mind, may be a bit unsettling at first.” (xi) Even so, they suggest that recognizing “such problems will only help readers better appreciate the efforts of serious biblical scholars to interpret the Bible. One goal [here] is to help Bible readers join the scholars’ quest for historical truth.” (xi) To date, I have read the first four books: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers, which maintain their order chronologically. Here’s what stood out: In Genesis, I learned theories on the origin of the word “Hebrew.” “The Habiru (also spelled Hapiru) were a class of fugitives found in the ancient Near East from about 2000 to 1000 B.C.,” although it’s unclear whether there is a link between these people and the early Israelites. Abram is first called a “Hebrew” in Genesis 14:13. “Although “Hebrew” is clearly an ethnic term in the Bible, it may have been originally a term describing the social condition of persons in flight or those in armed gangs. Abram could have been called “the Hebrew” simply because of his status as a foreigner in Canaan.” (23) I appreciated the sidebar commentary relating other traditions, stories and myths of the people groups of the time and how they differed theologically from the Biblical stories. Overall, the contributors point out that the pagan “peoples surrounding the Hebrews built their religious beliefs on the [recurring, regular] rhythms of nature” whereas “Israel wanted to tell how God had performed unique, one time actions in human history.” (xii) I found it striking how the narrative of Genesis changes -- indeed becoming more narrative-like -- when Joseph is introduced in chapter 37. So much detail about this man and a great example of God dealing with his creation in “one time, extraordinary moments of self-revelation.” (xii) In Exodus, following the narrative of the Israelites fleeing Egypt, I noted a stark shift to the extensive lists of laws and very, very specific requirements. I realized that learning about God without the Bible already must have been very challenging. The Israelites’ repeated failings and efforts to return to right living made me feel like they had to repeatedly stumble around pagan traditions to find God. My friend and I talked about this as an argument for the Bible’s as truth -- that if someone were to make it up, they wouldn’t have put all of the foibles and mistakes and sins in it! And women, for sure, wouldn’t have been the first witnesses to the resurrection. (But we’ll get to the New Testament in time.) When I got to Leviticus, I was struck by this verse: “If anyone sins because they do not speak up when they hear a public charge to testify regarding something they have seen or learned about, they will be held responsible.” (Leviticus 5:1) I wondered if there was a parallel between it and our current call to stand up to injustice, to prevent false accusations and “give people their truth back,” as in Bryan Stevenson’s expose Just Mercy. (quote from movie adaptation) I got a little confused in Numbers chapter 13 when the Israelites talk about how they can’t enter a new land because there are godlike people there. A sidebar refers back to Genesis 6:2 that talks about the sons of God, suggesting the possibility that sons of God mingled with sons of humans, creating a demi-god species. Certainly not something we covered in Sunday School! My friend looked this up for me and suggested they were either giants or fallen angels. She also directed me to Jude verse 6: “The angels who did not keep their positions of authority but abandoned their own home, these he has kept in darkness, bound with everlasting chains for judgment on the great day.” We wondered about the role of Satan and fallen angels and whether the introduction of temptation also allowed the introduction of choice, making our choice to turn to God out of love the entry point to a true relationship. I feel like I have only just cracked the cover in this new study, but already I agree with the contributors that what I read “may be a bit unsettling at first”! If you’ve made it to the bottom of this post, will you pray for my friend and I as we continue on this journey? Please pray that we’re able to complete it, and that through completing it, our faith may be challenged...and strengthened. Now, on to Deuteronomy!

0 Comments

“Oh, I wish I could write. It’s just so hard to fit it in with everything else going on.” Maybe I shouldn’t be surprised that this is often what I hear from people when I tell them I’ve been writing. We all could be writers if we wanted to be. As my kids’ teachers tell their students, “You are full of stories!” When writers tell me what worked to get them started, they mention attending a workshop or taking a class -- and being surprised by the quality of instruction even in community school continuing education courses. We need to be held accountable to our goals, whether that’s writing or otherwise. It’s too easy to get discouraged or distracted or both. For me, over the past year and a half, I have tried a variety of methods to stay focused on my writing. I found a stay-at-home mom buddy to write with semi-regularly. I signed up for classes that involved workshopping excerpts -- and consequently required continuous generation of new material. And from the first class, I was fortunate to find a group of women who wanted to continue to work together. Our writing group was born. What bonded us together? I think it was a combination of the desire for accountability, the belief in each other’s work, and the secret (perhaps not so secret feeling) that everyone else’s work was so much better than our own -- but perhaps I should just call that last one mutual respect. Last month, Belmont Books hosted members from a successful writing group to lead a panel discussion on what makes writing groups work well. Two of my own writing group members met me there to note takeaways for how to improve our system.

They advised their audience to keep systems but stay flexible. They shared their method of meeting once a month, with three people up for workshopping up to 25 pages each session. The rest of the group provides line edits and letter-written feedback, with everyone reading and commenting, whether they can make it to the meeting or not. The consistency over time has allowed them to understand each other’s projects and career aspirations, creating a space to address the needs of each writer.

They also supported each other outside of this format -- by celebrating publications and getting together as families, by reading double-length submissions of 50 pages at times to give overarching feedback on a manuscript. Above all, they stressed the importance of making sure everyone’s voice is heard. They also said that while forming the group or at times when deciding whether to add a new member, they ask themselves what perspectives are missing from the group (age, race, MFA background, family background). At the end of the session, my own writing group members and I felt pretty good about the rhythm and routines we had established for ourselves, meeting once a month to critique our ten page excerpts. We could use a little more diversity (we are all white women), but we are diverse in age at least, and in family background. We are a little heavy in the healthcare background, but what can I say, this is Boston! It was exciting to be in that room full of aspiring and active writers eager to plug in and be a part of the conversation, and I was surprised by how easy it was to start meeting people. If you feel like you have a story you want to share, I encourage you to try a workshop. GrubStreet has a free “brown bag lunch” writing series once a month, for example. Or call me. I’ll sit across from you in a coffee shop. We can dig in with our heads down together. Likely the hardest part is choosing to sit down and do it. The group will help carry you from there. “I never knew before that this wasn’t okay.” So said one of Ellen Pao’s employees after attending a session on “building a diverse and inclusive team and culture” (180). Employees described “ongoing harassment. Obscene recurring jokes. Inappropriate touching. All-male parties outside the office. A ridiculous number of messages to the team that included [references to female body parts]” (181). Ellen Pao didn’t grow up with a vision to work on issues of diversity and inclusion. She was raised to believe in a meritocracy, and for most of her life, as she worked hard (as an electrical engineer, a lawyer and then a businesswoman), she saw her efforts pay off.

To a young lawyer who doubts that women aren’t valued in the workplace, suggesting that if they weren’t valued, they wouldn’t be kept around in the first place, Pao retorts:

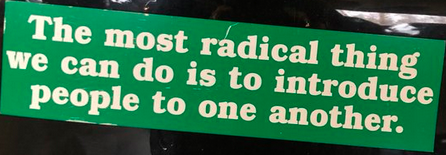

“If you had the opportunity to have a bevy of workers who were overeducated, underpaid, and well-experienced, that you could dump all the menial tasks you didn’t want to do on, that you could get to clean up all the problems, and that you could create a second class out of, wouldn’t you want them to stay?” (134) The lawyer is speechless. Following her dismissal from Kleiner Perkins, as CEO of reddit, a place that housed “an extremely popular porn website” where employees had to be coaxed to consider the removal of “revenge porn and child porn”, Ellen Pao initiated a series of workshops and interventions in order to increase diversity and inclusion at the company, workshops like those that prompted the employees to respond with “I never knew before that this wasn’t okay.” (195, 181) What I want to know is, really? You didn’t know that wasn’t okay? Is that what our culture has come to that we can’t even recognize when something is not okay? After sharing her story, Ellen Pao received stories of discrimination from all sorts of people: “Women who confided such stories in me sometimes shared things they had never told anyone else, not even their husbands; they were embarrassed and ashamed and horrified, even if they’d never done anything improper. They had been trained to keep quiet, to just take on the blame and hold themselves responsible for others’ actions. They’d thought they deserved bad treatment. My lawsuit, they said, proved that someone thought women deserved better. And it went beyond women. People from other underrepresented groups had similar experiences and reached out to me as well with their personal stories.” (bold italics mine) It seems to me that our culture needs love, and clear limits, just like the first good parenting advice I ever read. Like God really. Ellen Pao echoes this when she writes: “The uniform message I heard was that the community needed slow, deliberate changes, consistently applied rules, and action over words. We would make mistakes, and we should be ready to fix them quickly....We had to be consistent. We had to make it clear where the boundaries were. And we had to make sure our team was ready operationally and psychologically to enforce the boundaries.” (195) When you join a venture, do you ask yourself where is the love, and what are the boundaries? Probably not. It seems to me that either we assume love and boundaries exist, or we wander aimlessly, untethered by either concept. If those in the former group were raised with some kind of moral structure, whether grounded in religion or not, then what of those in the latter? Maybe in a culture where entitlement and fear of commitment leads so many to believe that the rules don’t apply to them, we lack the boundaries we desperately need. To reveal it in the extreme, read the words that one “famous public company CEO said on his deathbed, “Why do I have to die?” (120) I hope we don’t all have to have Ellen Pao’s experience before we find our voices. Are there spaces where you could make a difference? Start by defining your space. Then go, and fill it with love. For further reading on how you can learn more about these issues, consider Ellen Pao’s suggestions: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists Lindy West’s Shrill Susan Antilla’s Tales from the Boom-Boom Room Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures Eyal Press’s Beautiful Souls TED talks by Dr. Suzanne Barakat, Brene Brown, Susan Cain and Bryan Stevenson Projectinclude.org and medium.com/projectinclude “The most radical thing we can do is introduce people to one another.”

My kids’ old gym teacher had this bumper sticker on the back of her minivan. The first time I read it, years ago now, I nearly rolled my eyes. Over ten years on the East Coast will make you quite fine with remaining in your own bubble, only speaking to others if absolutely necessary. We don’t say hi when we pass each other on the street. We don’t even smile. I balk every time I attend an event requiring me to wear a nametag. If you don’t already know me, perhaps you don’t need to. Do you have any of this cynicism in you? You sure? The morning after I finished reading Ellen Pao’s book Reset, I felt pretty depressed about our default state to attend to our virtual lives more than our in-the-flesh, organic ones. For sure, I don’t naturally cross the room to learn your name, but in the past few years, I have witnessed the power of introductions. Sometimes, with all of my community organizing, I wonder what good I’m doing. Inviting people over for a party? Giving them space to discuss a book? What are we doing besides drinking wine and debating ideas without the pressure to attach them to action? Maybe we should take the time to be more productive in our various fields. Maybe I should get a real job. But then I’ll go to the birthday party of one of my kids’ friends, and a mom will tell me, “I didn’t know anyone at this school before I came to your house that time. I met so many people and it’s so nice to be able to say hi to them in the hallways during pick up and drop off.” Talk about wow. That gym teacher was right. We, culturally, spend so much time online living in virtual reality that taking the time to say hello face to face is nothing short of radical. So the other week, when I found a lost wallet on the sidewalk, I cringed when I realized that in order to conduct a thorough search for its owner, I should post my find on various social networks. I would have to use the networks that had let me down as I read in Ellen Pao’s book about reddit’s defense of free speech that allowed blatant porn use and allowed people not only to talk about but encourage their heroin habits. When did we sacrifice taking care of each other in favor of letting our demons run wild? But here I had a real world problem. I wanted to return the wallet to its owner. So I posted. A couple of hours later I was connected via email and phone to the owner of the wallet. One of the social networks had worked, but the avenue that solved the problem the fastest was actually my personal email list for my neighborhood book club. One book club member recognized the name of her neighbor’s mother who happened to be visiting from California. My own real life network solved the problem. I felt like my community work was justified all over again. I still hate nametags. But we wear them at every book club meeting, as a way to welcome newcomers. Since my kids are all in school now, I spend much less time at the neighborhood park and out in the community these days. Consequently, I meet fewer new faces. I have to remind myself to take extra advantage of the opportunities that come my way to make new introductions. It’s effort. It involves coming out of my shell. But I feel so much better when I run into you again, and I realize I already know your name. What about you? Feeling radical today? |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|