|

A few months ago, my writing coach told me about a call for papers at The Other Journal, which publishes pieces on themes at the intersection of theology and culture. “It might be a good fit for one of your chapters,” he wrote. Flattered and grateful, I took a look at the prompt. “...[W]e seek theologically infused contributions on the theme of reimagination...What aspects of traditional church life and practice need to be reimagined (and how?) in order to properly engage the challenges and nuances of our contemporary moment?...As always, we are particularly interested in...contributions that open our ears to the peacefully contrarian Christ by way of their distinctive style, ideas, and progressive consideration of the other.” I was intrigued and immediately began polishing a chapter from my memoir-in-progress. The chapter I submitted is called Cultural Infusion. A basic summary: A young evangelical mother is set on converting the Iranian Muslim woman from her kids’ playgroup, but after she has a chance to learn from mothers of other faiths, she learns how to stay true to her hopes while actively loving her new friend for who she is. Basically, the point of the piece is to reimagine how to engage in conversation with people who are different from me, especially when it is inconvenient or uncomfortable, and how the church could push people outside their comfort zones to make that happen. After I finished editing, I emailed it off and held my breath. I had done it at least. I had submitted a piece for publication for the first time. Two days later, I was surprised and elated to receive a positive response from an editor. He told me that my piece looked “promising” and asked me to provide a little “front matter” to include with it before he sent it to another editor for a second look. Sure! I cheered at my computer. I began completing the little worksheet but balked when they wanted to know my Twitter handle. Oh no, I thought. I might have to join Twitter. Long story short, I joined Twitter (@evenincambridge), and now I wonder if my lack of tweets and followers is the reason why I never heard back from them again. Maybe I should have just left that space blank and not tried to look hip.

From a Christian perspective, the story is a humbling reminder of the power of God and the daily failings of every one of us who claims to live for him. I had hoped that I had an amazing story to tell in my piece Cultural Infusion about my one-time Iranian friend who for one half-beat seemed curious about the church, but the way Nayeri captures his mother’s conversion reminds me of a story Tim Keller tells in The Prodigal God regarding a woman overcome to tears by new belief in the Gospel. As he tells it:

“I asked her what was so scary about unmerited free grace? She replied something like this: "If I was saved by my good works -- then there would be a limit to what God could ask of me or put me through. I would be like a taxpayer with rights. I would have done my duty and now I would deserve a certain quality of life. But if it is really true that I am a sinner saved by sheer grace -- at God's infinite cost -- then there's nothing he cannot ask of me.” Daniel Nayeri’s mother Sima reminds me of this woman. Sima knew there was nothing God couldn’t ask of her, and she gave up everything to follow him. The following is an excerpt of Sima’s conversion story. Spoiler alert here. But I think you will still find the book amazing if you read this first: “My mom was a sayyed from the bloodline of the Prophet… In Iran, if you convert from Islam to Christianity or Judaism, it’s a capital crime. / That means if they find you guilty in religious court, they kill you…. / [After his six-year-old sister announced she had decided to be a Christian], Sima, my mom, read about [Jesus] and became a Christian too. Not just a regular one, who keeps it in their pocket. She fell in love. She wanted everybody to have what she had, to be free, to realize that in other religions you have rules and codes and obligations to follow to earn good things, but all you had to do with Jesus was believe he was the one who died for you. / And she believed. “When I tell the story in Oklahoma, this is the part where the grown-ups always interrupt me. They say, “Okay, but why did she convert?” / Cause up to that point, I’ve told them about the house with the birds on the walls, all the villages my grandfather owned, all the gold, my mom’s medical practice -- all the amazing things she had that we don’t have anymore because she became a Christian. / All the money she gave up, so we’re poor now. / But I don’t have an answer for them. “How can you explain why you believe anything? So I just say what my mom says when people ask her. She looks them in the eye with the begging hope that they’ll hear her and she says, “Because it’s true.” / Why else would she believe it? / It’s true and it’s more valuable than seven million dollars in gold coins, and thousands of acres of Persian countryside, and ten years of education to get a medical degree, and all your family, and a home, and the best cream puffs of Jolfa, and even maybe your life. / My mom wouldn’t have made the trade otherwise. / If you believe it’s true, that there is a God and He wants you to believe in Him and He sent His Son to die for you -- then it has to take over your life. It has to be worth more than everything else, because heaven’s waiting on the other side. / “That or Sima is insane. / There’s no middle. You can’t say it’s a quirky thing she thinks sometimes, cause she went all the way with it. / If it’s not true, she made a giant mistake. / But she doesn’t think so. / She had all that wealth, the love of all those people she helped in her clinic. They treated her like a queen. She was a sayyed. / And she’s poor now. / People spit on her on buses. She’s a refugee in places people hate refugees, with a husband who hits harder than a second-degree black belt because he’s a third-degree black belt. And she’ll tell you-- it’s worth it. Jesus is better. / It’s true. / We can keep talking about it, keep grinding our teeth on why Sima converted, since it turned the fate of everybody in the story. It’s why we’re here hiding in Oklahoma. / We can wonder and question and disagree. You can be certain she’s dead wrong. / But you can’t make Sima agree with you. / It’s true. / Christ has died. Christ is risen. Christ will come again. / This whole story hinges on it. / Sima -- who was such a fierce Muslim that she marched for the Revolution, who studied the Quran the way very few people do -- read the Bible and knew in her heart that it was true.” (195-7) I dare you to find a conversion story more powerful. Really, I’d like to read it. Still, this isn’t the end of Nayeri’s story. Once Sima and her children escaped Iran, they stalled in Italy, where they waited for a country to accept them. Nayeri describes the suffering refugees endured from feeling unwelcome, where their Italian hosts would feed the refugees hot dogs so that they wouldn’t get used to the pasta and stay in Italy. As Nayeri’s friend in camp puts it, “They spend extra money just to tell us we’re not welcome.” (287) We all know the feeling of being unwanted -- from unrequited love or, as in my daughter’s case recently, from not being allowed back in a school building for 353 days -- but how do you suffer rejection when you can’t otherwise move forward with your life, when you are trapped in an eternal no man’s land? Yet, Nayeri’s mother found a way. At each roadblock, she found a way, and her son makes it repeatedly clear that she is the hero of his story. The Christian families who helped them, with schooling or with American sponsorship, played a role, and yet, while Nayeri makes it clear that he appreciated their help, their offerings come across as pretty pitiful. When we think of asylum seekers, do we understand where they are coming from? How much do we as comfortable American Christians underestimate what they are willing to sacrifice for their beliefs? Nayeri reflects: “I don’t know how my mom was so unstoppable despite all that stuff [meaning the physical abuse she suffers in her new American marriage] happening. I dunno. Maybe it’s anticipation. / Hope. / The anticipation that the God who listens in love will one day speak justice. / The hope that some final fantasy will come to pass that will make everything sad untrue.” (346) And yet, it’s not a fantasy, right? It’s written in Revelation that, “He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away. / He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” (Revelation 21:4-5) Do we believe that? And until then, in this life, what would we not give? What do we not owe him? What can he not ask of us? Read Nayeri’s book. Be humbled. Then ask what you can do for Him.

0 Comments

Can someone explain the genre “YA” to me? When I asked my husband what age range comes to mind when he thinks “YA”, he and I landed at the same answer: ages 11-14. Right? Except, when I looked it up, the official age range is 12-18. Still, given what I’ve seen lately from YA books, I feel like locking them away until my children are much, much older than that.

According to the Balance Careers.com, “The number of Young Adult titles published more than doubled in the decade between 2002 and 2012 — over 10,000 YA books came out in 2012 versus about 4,700 in 2002. ... In other words, the Young Adult book market is thriving.”

And it continues to do so. According to Publisher’s Weekly, “YA nonfiction, which is the smallest of the six major categories, had the biggest gains, with 2.5 million units sold in the first nine months of 2020.” And who is responsible for this boost? The article continues, “By some market estimates, nearly 70 percent of all YA titles are purchased by adults between the ages of 18 and 64. Of course, some of those are parents, but, assuming that the majority of actual young adults, who are old enough to make their own book purchases, a lot of "non-young adults" are reading those teen books. “ Flavorwire reported this stat: “It now seems clear that the healthiest market for trade books in 2014 includes adults who buy ebook versions of YA/Children’s books.” According to a 2012 study at Publisher’s Weekly, “More than half the consumers of books classified for young adults aren’t all that young. According to a new study, fully 55% of buyers of works that publishers designate for kids aged 12 to 17 -- known as YA books -- are 18 or older, with the largest segment aged 30 to 44, a group that alone accounted for 28% of YA sales. And adults aren’t just purchasing for others -- when asked about the intended recipient, they report that 78% of the time they are purchasing books for their own reading.” This 2015 article from The Guardian attempts to explain why, and they go beyond the simple ideas I came up with on my own. Like the fact that it’s easy reading. Just a little emotional ride. Entertainment. Right? But I wonder if this demand is creating inflated demand for authors to raise the stakes in their stories. Not only is there a growing trend to read YA, but I’ve also noticed a growing trend for books to address every buzz topic they possibly can and make the characters suffer every possible problem. I’ve also seen it in adult fiction, like Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half. Not only is it about race and class but also about sexuality and gender and AIDS. I made similar comments in an email to my fellow book club leader regarding Jacqueline Woodson’s Red At the Bone: “I feel like I want to read it again to understand the storyline better. On the one hand, I thought it was a bunch of routine coming of age / early pregnancy / things I had read about many times but put together in a somewhat new way. To throw in Greenwood, OK AND the Twin Towers AND the lesbian AND the gay high school friend all while being black just seemed like too many themes slammed in there for effect. But I suppose there could be a family out there who has and is experiencing ALL of that. I guess I'm not sure what to think of it in the end. I wonder if black and white audiences read it differently. I cried in a few places, lamented in a few places.” And now with Parachutes, it’s not just about race and class but also about sexuality and rape and all sorts of things I don’t want my soon to be young adult daughter to read about. The things in this book happen to people and they are awful when they do, but they aren’t a typical experience. I think our kids need more Beverly Cleary in the early years and Anne of Green Gables later on and the like in order to balance and gain perspective. But, you’ll argue with me, these stories are about promoting the marginalized voices around us. Yes, some of their stories are hard to read, but if you don’t pick up the challenge then you deny them their right to tell their story. Isn’t that what Debby Irving was talking about when I saw her speak a few years ago, when she suggested that “we are in a second Civil Rights Era, where the first one was about laws, this era is about lies...and now is the time for truth telling”? Is this the time to air all of our victim stories so we can move beyond them? Or is this doing our culture a disservice, along the lines of what the writers of The Coddling of the American Mind claim? Does any good come of this, for the characters or for the readers? In Parachutes, when the main character Dani finally gets to speak the truth about her debate coach sexually harassing her, she observes, “As I talk, I feel something change in me. I always thought that if I went out there and spoke my truth, I’d be filled with a kind of shame that I can never undo, but instead, I feel lighter. Like the crushing stone that has been weighing me down for months is finally being lifted. And the anger that has consumed me is morphing into something else -- hope.” (445) The other main character Claire, upon deciding whether to file a police report that she was raped or not, says, “I can never get my name completely away form rape...But maybe I can get it closer to, you know, justice.” (469) Perhaps what’s different here from the culture of victimization that is growing on college campuses (you really have to read The Coddling of the American Mind; or if you can’t, hopefully I will get around to writing an essay on this too), is that at least Kelly Yang’s characters attempt to solve their own problems in healthy ways. They attempt to solve them on a peer level first. Then they move to the platforms and review boards available to them. Then they file a police report. And through all of these steps, they remain nonviolent and remain secure in who they are, helping each other recover and move on from these awful experiences. The wide range of problems that authors are presenting nowadays aren’t “solvable” exactly. Endings don’t tie nicely in a bow. Still, the characters learn to support each other, and they learn to carry on with their lives. So I guess it’s not all bad. But I’m still keeping it under lock and key for another decade in this house. As the Balance Career.com put it, the YA genre is all about the emotional ride for the reader (“Whether a literal life or death struggle or a school crush story, the emotional stakes and the emotional intensity are commensurate with the raging hormonal intensity of the genre's intended audience.”), and, if you’ve been around a preteen lately, you know that you might want to think twice before fueling that fire. For now, in this house, we’ll discuss issues as they come up and work to expand our viewpoints, but we will work harder not to let our emotions overtake us. It’s too easy to give in to that fight. Christian youth programs ask kids to do some wild and crazy things. Take last weekend, for example, when I took my daughter to our second-ever mother-daughter retreat at Camp Berea on Newfound Lake in New Hampshire, where she asked me some really big questions, like: Having some fun draws the focus of 200 eyeballs to the center platform where a pastor can then explain how much Jesus loves us and how we can live for him. I also suggested that skits and challenges like that can help satisfy the developing brain’s need to do something risky and ridiculous while still staying safe. It’s why we try the high ropes course and rock climbing and kayak and canoe and play archery tag and maybe even shoot a rifle (you know, if you want to get really really crazy). And back in high school, it explained how when I participated in a volleyball and tug-of-war tournament in the church parking lot, I did so while standing in two-foot deep pits of squishy, squelchy mud. (I was still picking mud out of my ears weeks later.) And when you’re older, say, parent-age, it’s all so when you’re sitting out on the rocks at the edge of the lake during a lull in the action at camp that your daughter can ask you other questions, like, We clearly live in New England.

And also: Maybe this retreat was worth picking off the ticks and scratching those mosquito bites. All I could do in those moments was be glad that I packed my own insulated to-go cups so I could have an Earl Grey to sip on while I took a stab at answering her questions. What’s the point of God? God explains it all. He tells us who we are (his), what we’re meant to do on this earth (love God and love others), where we’re going after we die (heaven), how we’re going to get there (Jesus) and why he set this whole creation thing in motion in the first place (love). The when is the only mystery. All we can say is “in his time” and pray we have enough faith to believe that he will continue to fulfill his promises. But how do I know that God’s real? That’s a tough one. Tough to explain to my daughter whose brain is still geared toward absolutes. Tough because I can’t give her an absolute. Unless, of course, she turns out to be one of those people who reads scripture and just knows it to be true. This is, in fact, the very reason Luke gives when he writes his account of the gospel to Theophilus, which is a name for anyone who loves God: “Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. Therefore, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, it seemed good to me to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught.” (Luke 1:1-4, emphasis mine) Beyond Luke though, and throughout time, different people have found God in different ways, I explained. Some pray and see their prayers answered. Some are awed by creation. Some see other worldly beauty in art. Some believe God has intervened by sending friends and neighbors to them when they needed help. And some people look at their amazing children and know they can take no credit for the wonder they see. These people truly were made, were designed, were given. I also told her this: that this isn’t the first time she’ll ask these questions. Keep asking, I said. Never stop searching. And know that likewise, God will never stop reaching for you. He doesn’t get fatigued, and he certainly doesn’t feel the thigh burn after an epic game of capture the flag. He keeps going, keeps chasing, keeps loving. I’m not sure I can handle another night in a bunk bed, but from where I sit now in my bug-free kitchen, I’m thinking I should probably try, so that at the very least, once a year there’s a chance to sit on those rocks and check in. I could do more, I’m sure, but it’s a place to start. And God knows, every little bit helps. Our speaker for the weekend, Pastor Shaina Morrow, urged us mothers to fight for our daughters. “And when you fight,” she reminded us as she kneeled on stage, “you fight on your knees.” Mine may creak and my tight thighs may protest, but I’m going to get down there. And then I’m going to get down there again. I can picture only one black boy from high school. If there were other African-American students there, I don’t remember them. Maybe it’s just the passage of time and the passing of memory, but one thing I am sure of is that there weren’t many African-American students at my high school. There were some minorities, but I don’t know whether the staff at that time took part in discussions of how to teach across cultures. They must have been at least somewhat aware of the need, otherwise I wouldn’t have had that experience where I felt embarrassed when my own biases were tested. In other places, however, these discussions had been ongoing for sometime. Lisa Delpit first published her collection of essays on cultural conflict in the classroom in 1995, and between then and 2006, certain circles became deeply familiar with her work. As civil rights activist and academic author Charles M. Payne put it in an essay about Lisa Delpit’s work,

Delpit’s introduction to the 2006 edition laments the ongoing racism in our country as she reflects on the suffering endured by people of color after Hurricane Katrina. She writes:

“Since the publication of Other People’s Children, the country’s educational system has become caught in the vise of the No Child Left Behind Act, which mandates more standardized testing of children than the country has ever seen, with more and more urban school districts adopting “teacher-proof” curricula to address low test scores, along with school consultants whose sole purpose is to police teachers’ adherence to scripted lessons, mandated classroom management strategies, and strict instructional timelines that ignore the natural rhythms of teaching and learning. “But perhaps one of the changes that carries the most weight for all of us is the realization that we are not the country we once believed ourselves to be. The great putrid underbelly of racism and classism in our nation has been exposed through the tragedy of New Orleans. The horror of nature’s attack on a major U.S. city has been overshadowed by the distorted attitudes toward those who are darker and poorer.” (xiii) Lisa Delpit, a Harvard-educated African-American professor and author, whose own father died of kidney failure at the age of 47 when he was denied access to the dialysis machine due to the color of his skin, found a way to bridge the divide and elevate voices too long dismissed as emotional and anecdotal. Her work got the attention of stuffy research-based Anglo-academics and brought relief to educators of color. Delpit asks, “what should we be doing” to foster the education of African-Americans and other minorities. She writes, “The answers, I believe, lie not in a proliferation of new reform programs but in some basic understandings of who we are and how we are connected to and disconnected from one another.” (xxv) She continues, “I have come to understand that power plays a critical role in our society and in our educational system. The worldviews of those with privileged positions are taken as the only reality, while the worldviews of those less powerful are dismissed as inconsequential. Indeed, in the educational institutions of this country, the possibilities for poor people and for people of color to define themselves, to determine the self each should be, involve a power that lies outside of the self. It is others who determine how they should act, how they are to be judged. When one “we” gets to determine standards for all “wes,” then some “wes” are in trouble!” (xxv) Since then, and especially in the last year, the awareness of our white population to the racism and disparities in this country has grown immensely. Regarding what this means for the sphere of education, Delpit’s ideas have certainly become more mainstream. Scores of books are now available in the mainstream market that touch on these ideas. Take Beverly Daniel Tatum’s Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?, Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility, and Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist, among others. As a parent with kids in the public school system of a multicultural city, I can see how teachers come together to work at bridging cross cultural divides. They study together, conference together, and partner with families. Our city votes in people of color to leadership positions in a variety of settings, and our school system is no different. During our recent search for an interim superintendent, two of the three candidates were African-American, and when the one white candidate withdrew her application, I breathed a sigh of relief as it became clear that we would elect an African-American educator to fill the role. Our city has been criticized in recent years by its own high school students for struggling to walk its talk when it comes to hiring and supporting educators of color. And yet, through this search for an interim superintendent, one candidate mentioned the impact of Delpit’s book of essays on his career. It was following that interview that I picked up a copy and got a taste of the history of these issues for myself. If my family stays in this city for the long term, my kids will have an incredibly different high school experience from my own. During that same interview with candidates, one interviewer shared an incredible statistic on the state of multiculturalism in our city. I was impressed to hear that in Cambridge Public Schools, there are approximately 560 English language learners from 101 countries, with over 70 languages spoken in the district. Candidates were asked to present an action plan to create effective ways of communication between the district and school partners and the families of these students. As Delpit points out, there is work to be done on the tug of war between embracing Black English and/or Standard English and yet literacy in my kids’ community has ballooned into a much greater challenge. Yet, at the heart of this work, it is clear that Delpit’s mission remains, that our children’s success in education is very much tied to how well their teachers can reach them. I feel proud to be in a city where educators are trying. Our city and our lives are richer for it. When my first child was born, a well-meaning but inexperienced relative held her for the first time and spoke over her this wish: “I hope you never have to do anything hard in your whole life.” At the time, I instantly felt like I was in that scene from Sleeping Beauty where the bad fairy curses the child and the others struggle to mitigate the damages. Except, I was overreacting, right? My relative’s words weren’t ill-intended. Rather, I felt like I would be called a bad fairy if I were to suggest that there was something wrong with them. I kept my mouth shut that day but didn’t change my mind. It seemed like an awkward time to speak out about how challenges build character. I was also a brand new mother and understood I probably had a lot to learn about parenting. Still, now that I’ve had a decade of experience under my belt, and especially after reading The Coddling of the American Mind, I am more assured now that my instincts that day were right.

The ideas are:

The authors call these ideas “Great Untruths,” meaning each “contradicts ancient wisdom (ideas found widely in the wisdom literatures of many cultures)...contradicts modern psychological research on well-being…[and] harms the individuals and communities who embrace it.” (4) In their conclusion, they rephrase these messages: “Our argument is ultimately pragmatic, not moralistic: Whatever your identity, background, or political ideology, you will be happier, healthier, stronger, and more likely to succeed in pursuing your own goals if you do the opposite of [living these Great Untruths]. That means seeking out challenges (rather than eliminating or avoiding everything that “feels unsafe”), freeing yourself from cognitive distortions (rather than always trusting your initial feelings), and taking a generous view of other people, and looking for nuance (rather than assuming the worst about people within a simplistic us-versus-them morality).” (14) This book is so complex that I’ll probably use material from it in at least one other essay. Please read the book yourself and find the nuggets of wisdom that you can apply to your specific life stage, whether you have kids who are suffering under helicopter parenting, teens who are spending too much time on social media, or college kids who are crippling the right to free speech as they cry for protection. The authors begin with an evaluation of sweeping changes to childhood that have resulted from increased safety measures and overprotection at the expense of free play and room to develop problem solving skills. For example, they include a fascinating comparison of first grade readiness checklists. The current checklist consists solely of academic skills, whereas in 1979, an evaluation considered gross and fine motor skills, emotional readiness, attention span, communication skills, and whether a child could navigate their neighborhood alone. From what I’ve seen of public schooling through my kids’ experience over the past seven years, the teachers do encourage the kids in most of these areas, though kids need to be nine years old (not six) in order to walk to or from school on their own. Still, the expectations are largely centered around academics, and our kids’ days, by and large, in and out of school, are very structured. Let me digress to say that this book is not a yearning for yesteryear. The writers acknowledge that progress generally has been a good thing, and they remain optimistic that the strides we’ve taken as a society only bode for a brighter future. Yet, the authors recognize that there are problems with progress, meaning “bad consequences produced by otherwise good social changes.” (13) “We adapt to our new and improved circumstances and then lower the bar for what we count as intolerable levels of discomfort and risk.” (13-14) One consequence of this is general lack of free play for kids. Children without free play, they warn, “are likely to be less tolerant of risk, and more prone to anxiety disorders.” (193) On the other hand, if children are provided opportunity for it, “[f]ree play helps children develop the skills of cooperation and dispute resolution that are closely related to the “art of association” upon which democracies depend.” (194) (I include that last quote because their later arguments about struggling college students build off of it.) The writers quote an excerpt from a speech given by Chief Justice John Robets in 2017 at his son’s middle school graduation. He spoke on character, and his words are a thought-provoking counter message to the one I heard said over my daughter: “From time to time in the years to come, I hope you will be treated unfairly, so that you will come to know the value of justice. I hope that you will suffer betrayal because that will teach you the importance of loyalty. Sorry to say, but I hope you will be lonely from time to time so that you don’t take friends for granted. I wish you bad luck, again, from time to time so that you will be conscious of the role of chance in life and understand that your success is not completely deserved either. And when you lose, as you will from time to time, I hope every now and then, your opponent will gloat over your failure. It is a way for you to understand the importance of sportsmanship. I hope you’ll be ignored so you know the importance of listening to others, and I hope you will have just enough pain to learn compassion. Whether I wish these things or not, they’re going to happen. And whether you benefit from them or not will depend on your ability to see the message in your misfortunes.” (193) I was assured by now that I didn’t want my daughter to never have to do anything hard for her entire life. Rather, I wanted the opposite for my daughter -- enough struggle to know the pride of her own strength and ingenuity. Coincidentally, a day or two after I finished reading this book, I had an unexpected opportunity to try out these suggestions. Our day began painstakingly like our new normal -- setting up for a remote learning day and trying to wrangle kids bursting with too much energy. By 10AM we all had had enough, so I took my kids to play at a local forest preserve, hoping they’d get lost in the woods. I’m only sort of kidding because I think they needed as much space from me as I needed from them. And they also didn’t know they couldn’t get that lost -- they could experience the freedom of an adventure, and I was assured to (eventually) find them. In reality, they were out of my sight for about 30 seconds, and my heart was warmed as I heard one of my sons’ voices carrying through the woods (he can really project), “Guys, I can’t see Mom. I can’t see Mom!” So really, I wasn’t being negligent. That is what I’m trying to tell you. You have to know this before you hear the rest of the story. Shortly after that we bump into some moms and kids we kind of sort of recognize from church, from over a year ago back when we were going into the church building, families who have kids around the same age as my youngest kids, that it so say, mainly a bunch of preschoolers. After talking to the moms for a little bit, my kids and I meandered up a small hill where most of those kids were playing in a teepee constructed from fallen branches. It was clear to my family that those kids had been at it for a while and that they were feeling pretty territorial about a structure they hadn’t built but claimed as their own. It was also clear to me that my kids wanted to play in the teepee. This would take some negotiating. After asking the kids what they were playing -- “Emperors versus monsters!” -- and asking about everyone’s role, I saw our “in”. “So it seems like every one of you is an emperor or an empress. Where are the monsters?” The lead six year old shifted his feet, lowered his stick weapon, and dropped his defiant gaze for a moment before admitting, “We don’t have any.” I let him wait a second before asking, “Would you like some?” His face lit up, and, nodding at me, he said, “Yes!” “Great,” I responded. Then I turned to my own kids who were kicking dirt along the perimeter of the area, as if awaiting entry, and asked them, “Any of you want to be monsters?” “Yeah!” they all cheered. And amidst whoops of joy and fearless climbs up the external walls of the teepee, the battle began. At this point you also have to know that I wasn’t putting any other kids in danger. By the time my kids joined the game, the other eight or so kids were armed with substantial sticks but my kids hadn’t had time to find anything for themselves and there was nothing suitable left underfoot. They were going in with their grit alone. Now on a scale of kids’ games that require intervention, let’s say from one to ten, where one is a situation where any parent would be comfortable daydreaming or scrolling through a phone and ten is a situation where any parent would frantically call for an immediate and nonnegotiable ceasefire, this quickly escalated to an eight or nine. But having just read The Coddling, I wanted to test the truth of the free play theory. My kids were being attacked with sticks, but they hadn’t actually been struck. So for every cringeworthy near-miss, I repeated to myself, “No one got hurt. No one is hurt yet.” As I stood there watching the kids fight with all of their will, I noticed a change. My kids were fighting back in their own way, turning their fingers into magic lasers that could fire “blasts” at the emperors who chased them. I also noticed that if a child was chased, he or she could easily run to safety just a short distance from the structure. The kids were figuring out both their own boundaries and new rules of engagement. I was starting to become quite proud of them actually, “fighting” so well with one another that I was a bit startled from my reverie when one of the moms climbed the hill and, gesturing to the scene, asked in a tight, high-pitched voice, “Is this okay?” I sighed and then admitted, “I don’t know. I just read this book about free play though and wanted to see how it went.” The mom glanced back as one boy swiped at another with a stick, barely missing him. “Do you want me to say something?” she offered. She was so polite. “Nah, I was just going to let them beat the crap out of each other,” I told her. I don’t know if it was the notion that parents would actually let their kids fight that did it, or if she just didn’t like me saying “crap” where there were three and four-year-olds milling about, but her eyes flashed white and she called for an immediate and nonnegotiable ceasefire. See, I think it just goes to show how nicely the kids were playing that they listened right away. Then they stood around awkwardly for a minute or two trying to decide how to handle this maternal disturbance to their epic game. From where I stood, I saw emperors and monsters talking things over, yet not knowing exactly how to proceed. No one had a fallback plan per se. That’s when another mom walked over and with an apologetic tone asked, “Did we ruin it?” I shrugged. No, to intervene in one instance doesn’t ruin it. To intervene every time, on the other hand… Well, I couldn’t fault the mom who charged in. I’m sure I’ve done the same many times in the past ten years. And yet, now as my kids are getting older, and now that they are back in school, spending much of their time completely away from me, I have a new fear for their safety. I won’t be there to intervene, so I need to know they can take care of themselves and those around them. I want them to be able to wrestle with hard stuff and come out stronger on the other side. In their acknowledgments, the writers recall the psychologist Haim Ginott from the 1960s and his maxim for parenting, words that I will continue to test out in my interactions with kids. They go like this: “Don’t just do something, stand there.”

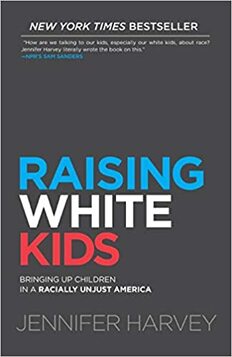

Recently, a friend mentioned that her husband was studying Raising White Kids as part of a church group, discussing it slowly one chapter at a time. Upon reflecting on the idea of how we choose discussion books I decided that oftentimes there is much sense in taking time to slowly digest new concepts or someone’s point of view. In this case though, I was glad I opted for my usual drink-it-down-as-fast-as-possible-to-get-to-the-next-book type of strategy. I mean, it isn’t my intention to make light of an author’s painstakingly crafted material; there is simply so much I want to know that I need to move along and try to process at pace. Jennifer Harvey’s book, though, was hard to read fast.

There are some books about racism that are hard to read fast because they stir up such strong emotions, mainly lament for the brokenness of the world. Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning is one of those. Books like that I have to put down and cry and try again the next day. This book was different though. The anecdotes of racism were still awful to read, but the bulk of the text is devoted to long winding and redundant phrases about systemic racism and complicity and culture that, to me, sort of floated above reality. If I were discussing this chapter by chapter with a group, there probably would have been weeks where I sat pretty silent during the meetings. While silence is definitely okay in some and in these specific circumstances, by reading the whole book at once I was able to extract the four or five practical take-homes. These fell into two categories: first, an explanation for why I balked at the title of this book, and second, how I was actually supposed to talk to my kids about racism. About three-fourths of the way through the book, Harvey describes the research of a sociologist named Mary Bucholtz who noticed that white high school “students are afraid that if they admit they are white without, in the same moment, demonstrating some reluctance about being white or without distancing themselves from white identity (that is, by mocking whiteness, or vaguely evading the question), they might be seen as endorsing racism. In other words, white identity and white dominance are so tangled up together that asking about one automatically raised the other. So they get silly, snarky, or tongue-tied when put in a position to have to say, “I’m white.”” (217) That idea really resonated with me. Just two weeks ago, I found my own mouth going dry when I had to answer demographic questions over the phone for the COVID contact tracer who wanted to make sure I had the resources I needed while one of my family members was in quarantine for being a close contact. I suspected that the contact tracer was herself Black, which made me feel strange to be put in a position where she might serve me in some way. I felt like as a white person I had already had plenty of opportunity to accumulate the resources I needed and if I didn’t have them now it was my own fault. I admitted that all four of my children share a bedroom, but I wasn’t going to say that was a problem. I’m also reminded of a time years ago, when, after reading Waking up White by Debby Irving, I found myself describing the book to an Iranian-Indian friend while sitting in the front seat of her car. Now I look back on that experience and am frustrated with myself for making another person of color sit through the tears of yet another white person waking up to the brokenness of the world. Harvey writes about this too. She (and the researchers she quotes) call this “disintegration,” a stage of racial identity one passes through on our way to having both a healthy understanding of ourselves and the racial injustices of the world. As she describes it, “...white people tend to believe things are racially fine in society and that our collective declaration of “Everybody is equal” actually describes the way things are… / It’s inevitable, however, that at some point white people will encounter experiences in which people are treated differently because of race. So such dispositions and beliefs begin to ebb. When we have such encounters at a frequency or intensity with which they can no longer be ignored, the prior “naive belief” that race is not meaningful starts to disintegrate.” (107) This explains the jolt we feel after a violent racist act and why we suddenly feel the need to act. Harvey says this response is good because it allows white people to realize that they have a personal stake in antiracism. She states we can’t just fight racism for POC as this “lead(s) us into actions that are patronizing, condescending, or otherwise fail to recognize the full humanity of people of color.” A shift in thinking “may also signal a move from guilt to anger -- a kind of healthy moral anger at injustice and an outrage that people of color are being harmed, combined with the recognition that it’s being done in my name.” (118) Whenever Harvey claims that all whites are complicit in racial injustice, I bristle, and have trouble teasing out why I should once again feel like I’m a bad person and that I should be emotionally charged for crimes I didn’t commit, like the European takeover of American land and subsequent exploitation and genocide of African Americans and Native Americans. At first glance, that seemed like a tall order to me, to place the burden of hundreds of years of injustice on the shoulders of all white children (and their parents) in order to accomplish...what? There are more dots to connect here -- between those blatant crimes of “long ago” to the subtle and outrageous injustices we see every day. Harvey’s goal in this book isn’t to tell you which injustices to speak out about or act upon. Her suggestions are more subtle themselves and involve brainstorming a mental framework for how to approach situations through a racial lens. First, Harvey teaches what I’ve heard several times before now, that there is a great difference between how people of color and whites speak to their children about race and equality. In general, people of color talk about race whereas whites don’t. More specifically, “[i]n contrast to “the talk,” for example, a one-dimensional teaching becomes “police are safe; go find one if you are in trouble.” In contrast to “we should all be equal, we all have equal worth, but we don’t yet all experience equality,” a one-dimensional teaching becomes “we are all equal.”” (8) How to achieve this new perspective? Harvey rejects a color-blind approach which has been our culture’s default for many years, and she argues that while a move to appreciate diversity is “nice”, it hardly gets the job done. Her goal is something different, something she calls race-conscious parenting: “Race-conscious parenting acknowledges, names, discusses and otherwise engages racial difference and racial justice with children. It does so early and often. It assumes that antiracism must be a central and deep-seated commitment when it comes to how we parent white children and in what we want them to learn.” (18) What does this look like in practice? From her examples, it means teaching about the complexities of policing in this country and how some children might not want to go to the police for help. It means calling out the fact that we don’t experience equality even though we want it. It means acknowledging the attributes in George Washington that we admire...and acknowledging how we wish he had been different, and how we wish others had spoken up for those he enslaved. In terms of our everyday actions, Harvey shares a concrete example of parents being unsure of the effects of their teaching but there being clear results. In this case, Harvey’s seven-year-old black nephew was playing on the playground with a group of mostly-white kids when one of the white kids “pointed at him and said, “Your skin’s the same color as poop!”” Another white child “started yelling... “Hey, that’s racist! Hey, that’s racist!” (146) The author describes how hurt her nephew was by the racist remark but that he also saw a friend stand up for him. After they had heard what happened, the defender’s parents were proud of their son. They also admitted they were trying to have conversations about racism at home but weren’t sure what effect they might be having. What a great example of speaking up in a small but deliberate way, of starting in your own life instead of feeling paralyzed by the thought of trying to cure society’s ills at large. And there were further effects. Harvey concludes that she suspects that her nephew “left the situation less isolated and alienated than he would have had he been left to only receive comfort from his parents…[and that the white friend] left the situation more empowered to act against racism again next time. [Harvey also knows] the bonds among the parents were strengthened: [the white friend’s] parents heard that their parenting choices had positively impacted [the nephew], and [the nephew’s] moms experienced parents in their community taking seriously their responsibility to equip their white children to live out solidarity with their Black son.” (147-8) Having just read The Coddling of the American Mind in which the authors discuss the increasing tendency of college students to engage third parties in their disputes, I like how in Harvey’s example, the interactions all happened on a peer level, without intervention or necessity of third parties in the moment. As she discusses how to implement anti-racist attitudes and actions, Harvey discusses the more complex journey of building a healthy white identity. The author’s goal for how healthy white kids view their identity is for them to be able to say: “I’m white, and I’m also an antiracist-committed person active in taking a stand against racism and injustice when I see it.” (234) When talking about her wish for her daughter to understand “the gap between herself, even as a white person, and racist systems,” Harvey “invite[s] her to strategize how she can actually make that gap even larger through active, antiracist behaviors. / The gap I’m describing here is the same one Bucholtz’s white students unsuccessfully tried to create by rhetorically evading Bucholtz’s question about racial identity. As parents, we need to support children in creating distance between “being white” and “racist” in larger contexts in which these are conflated.” (226) Those important messages are in there, as is so much more, so I think I still recommend this book. There is no one experience or author or book that’s going to cover it all. Similarly, there is probably no one we will agree with completely. As my husband says, “reading books that make us uncomfortable is how you avoid coddling your own mind.” But I think there’s a lot to learn here. I’m going to have to make some assumptions about the authors here while I make this next statement, but I am going to venture that the authors of The Coddling and Raising White Kids share similar ideologies and hopes for the kids in our country. Also, they are all white. And while they aren’t both about racism, they are both about teaching kids how to think about themselves and others and about how to work together. Still, they approach it in very different ways that demonstrate one example of how our different personalities and backgrounds are going to have to work together to solve our society’s greatest problems. Bottom lines? White parents and kids can be white and antiracist. We should talk about race early and often, and we should keep the faith that there is something we can do to shift the culture, today, in our own lives. Last spring during the first wave of the pandemic, I wrote about my mixed feelings over wanting to help. I used to be a doctor, so I felt somewhat guilty not being employed in the medical field where I could serve on the frontlines. I felt like I had abandoned my skill set. I also had to admit that I wanted to be the hero and stick my neck out there and actually do something, as opposed to following orders to shelter in place. On the other hand, part of me just wanted to hide in the closet until this whole thing went away.

This school year, as my children have at times and increasingly spent more time in the physical classroom once again, I have also felt like I have shirked my responsibilities as a room parent. I wrote about my new role almost two years ago on this blog. I was intimidated from the beginning. Room parents have the potential to add so much to a classroom. I don’t feel like I did that in pre-pandemic times, and in the last year, I have definitely taken a backseat approach. Other parents have offered up wonderful ideas for community building, teacher support or space improvements, ideas like special thank you notes, organizing our own picture day, or cleaning shared outdoor equipment. These are all wonderful things! And yet, with each suggestion, I cringed. How would we do it safely? Did it really need to be done? Were we just creating busy work for ourselves? If I could connect these two observations about myself over the course of the pandemic, I feel like it suffices to say that I wanted to act and yet felt paralyzed from doing so. I became sick of my home surroundings and increasingly interested in spending time out of the house, and yet, in what capacity? Return to work after over nine years? What kind of work? And what if my kids were forced to quarantine and I had to break commitments? It occurred to me, slowly and then all of a sudden, that the pandemic had recreated the emotional place I was in three years ago when I first sent all of my kids off to school. Back then, I wrote about how I felt overwhelmed by everything I had been putting off and everything I wanted to jump into all at once. I now had a desperate need to be out of the house on top of my desire to reinvent myself by finding a new career or some kind of work to be involved in. Then, as we anticipated school days expanding to five days full time, I got that dreaded phone call: One of my sons needed to quarantine for a positive case in his classroom. And all I could think was, there will be no end to it. Our house hunt had thus proved fruitless, my weak writing projects bobbed like little leaf boats on the waves without direction and now with a child at home again, I searched for an emergency eject button. Oddly enough, my escape route channeled me directly into another elementary school. Not as the PTO president. Not as a room parent. Not even as a parent. Hearing the desperation in my voice, a friend of mine connected me to her kids’ school principal who had put out a plea for help watching the kids at lunch and recess. And that is how I became a lunch and recess monitor. “So, why do you want this job?” the principal asked me over the phone. “You’re kind of overqualified.” “You know, I’ve been thinking about my motivations, and it comes down to this: I need to get out of my house.” And you know what really got me the job? Well, two things: the principal was desperate. And second, she heard the seriousness in my voice. I would be there and on time because I couldn’t stay home another day. This role, interestingly enough, has also fulfilled my desire to help during the pandemic. Kids have silently shouldered the burden of remote schooling, all the while suffering from loneliness and anger issues in the most mild cases, and I wanted to help fill a gap. Anything to keep the schools running. Plus, I get to carry a walkie talkie and wear a whistle. Now that I have twelve shifts under my belt during which the kids have reassured me that I hold absolutely no authority, I feel like I’m doing it for another (or maybe a second) reason. Today, after I collected what soccer balls and jump ropes I could find after a blustery time on the blacktop, I returned the equipment to the gym, bursting to share my realization. And here’s the thing about going into a workplace: There is always that random third party who will listen to your little stories throughout the day, which is pretty cool when you think about it. So when the gym teacher looked at me and asked me how the day was, my voice echoed off the chambered ceiling as I passionately proclaimed, “God bless teachers.” She chuckled. “It’s not easy. You’re doing great though. Thank you for being here.” We exchanged masked smiles and waves before I santitized my hands for about the five hundredth time in my three and half hour shift and headed out. Now that it’s (finally) quiet in my house for the night, I marvel at life’s twists and turns. “You know I’m making more per hour than I did as an intern physician?” I asked my husband the other day. “Really?” He looked skeptical, thinking of my new minimum wage job. “Yeah, well, any salary isn’t much when you divide by one hundred hours a week,” I clarified. “Oh, right.” He chuckled and shrugged. It’s not really a career move, but it gets me out of the house. Bottom line though, it’s a thing I can do as we look to move out of this pandemic. Bring on the vaccines for kids. Let’s get there. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|