|

This month I wrote about the suffocation of coronavirus...and of isolation… But unfortunately, the inability to breathe freely this season didn’t stop with those issues. Coronavirus, isolation, and police brutality? I decided to listen in to learn how the crises of this season were affecting the Black community in Cambridge. During the coronavirus pandemic, Cambridge School Committee Vice Chair Manikka Bowman and former mayor and sitting City Councillor Denise Simmons began to notice that minorities were three times more likely to become infected with the disease. Why was that? They cited underlying medical conditions, unequal access to healthcare, and employment in essential services as leading reasons. It is clear that even in a city as progressive as Cambridge, we still have a long way to go towards equity. In response to this disparity, these two courageous women initiated a series of panel discussions about how the pandemic has affected the Black community in Cambridge, covering topics like education, mental health and an intergenerational conversation on the intersection of COVID and racism. I listened in, and this is what I gathered from the first three of these probing conversations: First, the Black community has sayings I have never heard before. Sayings like, “If every hand that reached, could touch…” referring to the inequities facing Black Americans who often find themselves on the other side of a locked door. And perhaps, more specifically as it relates to contagious disease, “When everybody else gets a cold, we get the flu.” Or, in this context, getting affected by COVID at a rate three times greater than whites. Dr. Jeanette Callahan of the Cambridge Health Alliance shared that new studies in epigenetics (the study of changes in heritable gene expression due to environmental factors) suggest that underlying conditions like vitamin deficiencies, as well as inherited genetic changes from “internalized trauma,” the results of multi-generational struggle, effectively amplify the vulnerability of this population. Mental health workers further spoke of the stigma of mental health issues within the Black community such that people are prevented from receiving the emotional support most have needed during this time -- even as much as a “how are you today?” Educators notice changes in their students: high anxiety, disconnection, worry about family members who continue to work as essential workers, lack of IEP services, new responsibilities like taking care of younger family members or doing the cooking at home. Community partners like Becoming a Man, Workforce, Cambridge Families of Color Coalition, My Brother’s Keeper, Building Equity Bridges and the NAACP have tried to fill the gaps by providing space to support the mental health of their students. They have also worked to provide information on meals available through the Cambridge Public Schools as well as guidance for how to access the Mayor’s Disaster Relief Fund. But they kept hearing from people, “we are too scared to leave the house to get that food.” Also, they heard, “It’s hard to engage in teaching or learning when you’re wondering, how does this make a difference in my life right now?” First they encouraged people to pay attention to their bodily needs -- for exercise, rest, even a warm bath to help relieve the stress. But then they got serious about education. Let’s provide a variety of resources for these students -- these scholars -- who need an array of options to meet their needs, because we don’t want to be any further behind when we return to school, they said. They called for an elevation in language (as in referring to the students as scholars) as well as expectations to combat the status quo that has perpetuated grossly unbalanced academic outcomes between white and minority students in the district. Educators and community members encouraged families and parents to use their voices and give feedback so that the system can give them what they need. They noted that the school system can change faster than we thought it could...and perhaps now is the time to leverage that momentum to make changes toward equity during this time. Vice Chair Bowman also announced new funding to be dedicated to hiring additional social workers for the district, in an attempt to fill the gaps. More guidance counselors may also be hired. More counseling of course, because during the time between the first panel discussion on May 24th and the third panel discussion on June 21st, things heated up across the country for another reason. COVID has been an accelerator for the conversation about racism. Perhaps it’s the lack of sports or other distractions that let us put it off until later, as one Cambridge father mused. Whatever the reason, progress wasn’t going to be made until people made it a priority, but more and more people are stepping up to act. Multiple panelists began to call for Cambridge to declare racism a public health emergency, as Somerville did recently, with Mayor Joseph Curtatone stating: “"No one should fear for their lives because of the color of their skin. No one should have to grieve the loss of a loved one, friend, or stranger who died because they were black. No one should have to fear those who are sworn to protect and serve." Panelists responded to parents’ questions about how to discuss recent events with their children, advising age-appropriate conversations first, but that when the time is right, to educate each other on the history that hasn’t made it to the textbooks yet. And when you have shattered their reality, then, they said, “be prepared to love your child after the conversation, because you won’t be able to answer all questions.” Panelists also discussed how to safely attend protests during this ongoing pandemic. The Chief Public Health Officer for Cambridge reminded people to take precautions -- mask up, stay six feet apart, think about getting testing for coronavirus afterwards. Other panelists encouraged people to think about what else they could do besides attending a protest -- encourage Congress to provide PPE for protesters, sign petitions, or use apps to fill up Trump’s rally with phony attendees to falsely elevate attendance levels... The most recent panel discussion took place during Juneteenth weekend, the holiday commemorating the announcement by federal soldiers in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865 proclaiming that all slaves were now free. Several Black panelists were unaware of Juneteenth prior to college or adulthood. Two cited the show “Blackish” as the source of their knowledge. But as community members caught on, they enjoyed the celebration in front of the Main Library, hosted by the Cambridge Families of Color Coalition, and began to think of Juneteenth as a time to remember that, in the words of one high school student, “no one is free until everyone is free.” The holiday has been elevated to attention lately, and recognized, as HR Strategist and Cambridge father Jeff Davis put it, as “a reclaiming of the stories of escaped slaves and sharecroppers that have been taken from African Americans for over 400 years.” Ken Reeves, the President of the Cambridge chapter of the NAACP pointed out that Cambridge declared Martin Luther King, Jr. Day a city holiday ten years prior to it becoming a federal one. Panelists hoped that they could take the lead on elevating Juneteenth to that same level, referencing it as a focal point to address racism in this country. Panelists also referred to the impact of hearing Frederick Douglass’s 1852 speech “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” which will be read as part of Cambridge’s 4th of July Celebration later this week. Some bottom lines and takeaways from Ken Reeves, President of the NAACP Cambridge: For our nation: “Black hearts need to be unburdened. And white hearts need to change.” For Cambridge, in particular: “We always thought we had a safety net that would catch everybody, “but due to front line jobs or overcrowded living situations where they can’t socially distance,” Black Canterbridgians are disproportionately affected by COVID. Some next steps that were suggested as discussions came to a close: -Invitation to participate in a new task force to reimagine how to open schools again. -Invitation to School Committee and City Council meetings. -Push for racism to be declared a public health emergency. -Learn the real history, write it down, and pass it on. (Follow the 1619 Project in the NY Times Magazine.) -Give thermometers to every family -- make them feel seen. -Maintain physical distance; keep each other safe. -Consider anti-racist strategy like this: First, name racism. Second, ask how is racism operating here? Then, organize and strategize to act. If any of this was uncomfortable or difficult to read, remember that the first goal here is to listen. Just listen.

Click here to view the previous panel discussions: bit.ly/2M6DELL

Listen in. You may feel like you’re not accomplishing anything. Tell those thoughts to be quiet. Then, hear these panelists, and make their story a part of your story. As the Cambridge NAACP President Ken Reeves said in closing, “Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid or terrified because of them, for the LORD your God goes with you; he will never leave you nor forsake you.” (Deuteronomy 31:6)

0 Comments

One of the surprises from this time of isolation due to COVID has been how frequently my friends and neighbors have asked me about my church’s response. In the beginning, people I didn’t realize even knew I attended church started asking, What’s your church doing? Are they still meeting for worship? Are they moving online? And then, as Massachusetts dipped its toes into reopening plans, What’s your church going to do? Are they reopening?

I have to admit that I was a little upset with my church’s decision to close their doors even prior to the State mandate to do so. In closing, they were disrupting my small group’s meeting time. They were depriving me of that weekly spiritual renewal time when we gathered for worship. I mean, there’s a reason we call our worship space a sanctuary! But then, especially as the pandemic worsened, and as ambiguity faded into the background, the other congregants and I felt new purpose in our mission to stay home in order to keep others safe. Our church was also conveniently technically advanced, and we didn’t even miss a Sunday service as the staff swiftly switched the entire program to YouTube. That first week with the kids home from school, our Sunday School leaders initiated a kids’ program for connection, worship, and study that met three times a week for several weeks before they morphed the program into Wednesday afternoons and Sunday mornings. My kids wondered, “Why are we doing extra church now?” And I was all too grateful that in the sudden void of our daily routines, our spiritual leaders were providing guidance and community during unprecedented and uncertain times. My church also initiated a pun-filled and entertaining YouTube series called “Hope and Soap” where pastors interviewed church members and attendees about the work God was doing through them during this time, work that served to bring hope to us all. I wrote about this briefly from another angle in my post Rethinking Fight Strategy. And yet, about a month ago my church discontinued its installments of “Hope and Soap.” Not because they had lost hope. Rather, they felt God shifting their focus, and all of a sudden I started hoping people would ask me this: What is the church doing about racial inequality and police brutality? And yet, while I had opportunities to share with friends and neighbors, no one sought me out to begin this discussion. Today, I want to remind church-goers and non-church-goers alike that we want to be held accountable to anti-racist work. Within my church, as within many churches across the country, all of a sudden, our services were filled with space to lament and grieve the deaths of Black people. And we revisited our shame that these disparities aren’t yet resolved...even within the walls of our own church. How had we let things continue in this way? When I first started attending my church there was an African American woman pastor. She left the congregation about five years ago in order to fill a position on staff of our denomination, and since she left, we have had no Black Americans on staff. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously stated that “it is appalling that the most segregated hour in Christian America is 11 o’clock on Sunday morning.” I have always considered my church highly diverse (and I learned the above quote during a Sunday sermon!). Yet, while I can find people of all colors, we are predominantly half white and half Asian, with a smattering of Latinx and Black people. And among the leadership staff, there are clearly some folks missing from the table. During the last month or so, my church has started to listen to folks outside of its bubble, including engaging Black voices in conversation during our services to provide perspective and teaching. As the protests continued, I listened up as my church interviewed college students about how they saw God calling them to be a part of an anti-racist movement. I joined the tail-end of a Zoom meeting when one of the pastors hosted a presentation on the intersection of protesting and violence by Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson, Professor of Africana Studies at Wellesley College and author of Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence. And when several members of the Cambridge branch of our church organized a “Teach-In,” I was an attentive witness as six presenters shared history and personal story of the intersection of racism and a variety of topics, including education, transportation, Asian-American identity, technology, the relationship between protesting and violence and yes, racism and the church. That last one, of course, was particularly hard to hear. None of the information was good. In fact, as we defined our emotions entering and leaving the Teach-In, the word I brought with me into the space morphed from “curious” to “heartbroken”. How could I look at images of white women in front of their church holding signs saying “We do not welcome the colored” and not be? How against the message of Jesus is that? But wait, there are Black people at my church. We must be beyond that, right? What I am learning is that if a Black person says he does not feel seen, we need to stop telling him we see him. If he’s saying “I’m hurt,” we need to stop saying, “It’s not my fault.” Instead, we need to ask him what we can do to help. In the case of my own church, one starting point would be to hire Black leadership. For several Sundays, we have been reviewing the verses in Revelation that couch Jesus’s salvation not as just a personal salvation and entry to Heaven, but a salvation for all tribes and nations to heal and come together. And yet, just as we strive to work out our personal salvation on earth prior to death (rather than not care and just go on sinning without confession), we feel the Biblical call to work out our corporate salvation as well, to do the work on earth to reunite the different peoples of the world. As Revelation 7:9-10 says, “After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands. And they cried out in a loud voice: “Salvation belongs to our God, who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb.” As we study these verses, we come to understand that God doesn’t want us to be colorblind. He wants us to celebrate the diversity among us, to lift up every race, ethnicity and language, so that we can all sing praises to God together. What is the church doing about this? Probably more than I’ve listed here. What could the church be doing about this? More than I’ve listed here. And if we don’t know where we should begin, let’s continue to listen, to learn the history previously unwritten in our textbooks, to amplify the voices that have been silent for too long. That’s what my church is doing about this. The following is a list of books and organizations that are engaged in anti-racist work. The presenters on the Teach-In encouraged viewers to read and donate as they are able. While I have read and can encourage the reading of Beyond Colorblind by Sarah Shin, I have not read the other books, nor have I learned about the other organizations in depth at this point. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code by Ruha Benjamin The Coded Gaze, documentary, Joy Buolamwini (2018) and TED talk https://www.8toabolition.com/ http://d4bl.org/ Beyond Colorblind: Redeeming Our Ethnic Journey by Sarah Shin TED talk by author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie https://www.massbailfund.org/ https://www.massundocufund.org/ https://www.ujimaboston.com/ https://www.redistributionfund.org/ Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire How to Be an Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism and You: A Remix of the National Book Award-winning Stamped from the Beginning by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi I know some people wonder if this virus is for real, but I was surprised to receive a letter from a friend declaring, “Enough already; let’s trust in God and get back to work!”

I’m sure we are all familiar with compassion fatigue by now. Even in places that have been hit hard. But to insist that things return to normal is to turn a blind eye to suffering. To some, numbers are meaningless. But, in case it’s useful, to date of this writing, the City of Cambridge has reported 1,094 people infected with coronavirus...and 97 deaths. Months ago, when I sent the following pleading email to a friend in a lesser affected area, the numbers were smaller. To those who wonder whether we should take precautions against this virus, consider my experience in Cambridge, a city that has suffered, yet suffering much less than many others during this time. I also share this knowing that my story is a privileged one -- that of a family able to self-quarantine while maintaining income and physical health during this time. Dear friend, I know you as a person of faith, so before I forget, I wanted to pass along a link to a printable book (that your kids can color). A friend sent this link to me. It's by a Cambodian writer who is trying to educate kids about coronavirus and how we can focus on Jesus as we keep others healthy. When I first started hearing about coronavirus, I got in touch with my friends who have family in China and Iran. They said their families were okay, thank goodness. Then, a neighborhood dad suggested quietly that we start stocking up on non-perishables. I figured I'd get around to that once I got through my kids’ birthday party...and a bunch of other stuff I had going on. Then it got bad in Italy. And they closed schools here on March 13th and closed playgrounds on March 17th. And I was asking my Italian friend how her sick friend in Bergamo was doing. And I was seeing grocery shelves absolutely bare and worried about how I was going to feed my family. And my husband worried about getting sick and being out of commission when he was in the middle of a job transition. And I worried about how I was going to implement school structure at home so my kids wouldn't fall behind when my kids were completely balking at the idea of me as their teacher. And then the first person in Cambridge died. And then people in their 40s died. And each of us wondered if we would be next. And then friends who are healthcare workers got pulled away from their usual jobs to work with COVID patients, placing themselves and their families at risk. I mean, oncologists working as internists? We have heard of the hospitals being at max, of auxiliary locations being at max. I pronounced 20 patients during my one year medical/surgical internship. And it completely wrecked me mentally. I can only imagine the grief and overwhelm that the healthcare workers in Massachusetts feel as they pronounce 150 people DAILY. I understand why the physician in NYC killed herself. 3000 deaths a day?! Morgues in the street? I understand the situation is different where you live. I regret that this is yet ONE MORE divide in our already far too divided country. I couldn't sleep last night thinking about your perspective. Yes, we have all had our purpose in life derailed. Yes, we are all angry. Yes, we all want to get back to normal. But we aren't not trusting in God. Our church closed its doors before it was ordered to because we wanted to protect the most vulnerable around us. We didn't close out of fear but out of love for our neighbors. Everyone who has work is working harder than ever before as they try to adapt to this work at home situation. Everyone who doesn't have work is....well, I hope they are all right. I really hope they get some assistance. I know our city is trying to provide multiple outlets of assistance to those struggling. I still can't get everything I want at the grocery store. I shop every two weeks and hope it lasts. But I'm not afraid of dying anymore. I never really was. But I was afraid of giving the virus to someone else and having to live with that. And so many people I know either have pronounced someone dead of the disease, have witnessed illness close up or from afar, or are similarly afraid for their frail loved ones. There have been 55 deaths in my city. We don't know the mortality rate. That is clear. But we do know this virus has killed very quickly. We have tried not to overwhelm our hospitals but our medical workers are overwhelmed. And I need to know that this is worth it -- this sacrifice we're all making. There's no way to go back in time and keep the schools open and put our senior citizen aged teachers at risk and wonder how it would have turned out. We have to believe that we did the right thing, trying to protect everyone. It's now illegal to leave the house without a mask in my state. It's extremely inconvenient. I have been grieving and angry and a terrible parent and teacher for my kids. I have been a terrible wife. But then we come back together as a family and read "King COVID and the King Who Cares" and we think about why we are doing this, who we are doing it for. I trust in God to get us through. I trust that he will give the scientists wisdom to create a vaccine to let us continue to function. I trust that he will bring people to him during this time. I understand it's really hard to see this as anything but inconvenient when you don't know people on the front lines. And, as in so many areas, I wish we could do a better job of drawing sympathy for the hurting...whether they are hurting from COVID...or from hunger or from unemployment or illegal immigration or any other hurt in life. Is this violating the Constitution? I don't know, but I have felt like this is an emergency situation. We're all frustrated that it's becoming apparent that no one knows how to get us out of this situation. That is really hard. I just screamed at my family repeatedly before I sat down to write this. Is that the cost of this pandemic? Will we rise above that? I am suffocating from lack of space. But some people, hundreds daily, are suffocating from COVID. Who am I to put them at risk? With God's help, I can do this. As a high school student, I attended a workshop where I was asked to silently visit several stations around the room, look at the exhibit, and record answers to corresponding questions on a piece of paper. I do not remember the context or name of this workshop, but one fragment of it is burned in my emotional memory. I approached one of these stations and found two 8x10 laminated photos -- one of a white man and one of a black man, both middle aged and professionally dressed. I read from the paper in my hand: Before turning over these photos, decide in your mind which of these men is a criminal and which is a Nobel laureate. Record your prediction here, and then read the bios on the backs of the photos. I glanced back at the photos and felt myself fill with burning shame. I was sure my classmates who progressed through the stations around me could feel the heat of that shame radiating into the room. I was sure they would see my face turn ten shades of red. I decided not to record my predictions, and, ever the good student, I felt even worse for cheating on the assignment. I did not want to be honest and reveal that I thought the black man was the criminal, because I had a strong hunch that the point of this lesson was to teach me that I was biased.

Growing up, I didn’t know any Black people. And I didn’t know any criminals. Both belonged in the “other” category, so perhaps Black and criminal were the same? Is that how I made the mental leap that day in high school when I suddenly knew my assumptions were wrong? Or, were my biases based in the glimpses I stole of the evening news, when I’d pass by the TV in the kitchen where my mom would be cooking dinner, myself never really watching or understanding, just knowing that if someone was going to be arrested, that person was going to be Black?

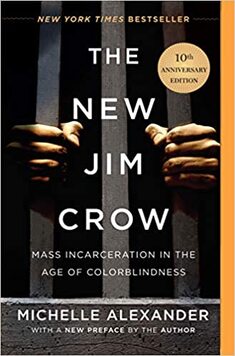

More recently, in response to reading Debby Irving’s Waking Up White and Finding Myself in the Story of Race, I began to notice how I flinched when a black person flagged me down from inside their car. How much shame did I feel when I noticed that the person was my kids’ faithful school bus driver? Or even worse, when I realized the person was my neighbor, whom I should have recognized? In The New Jim Crow, Ms. Alexander details the detrimental causes and effects of the system of mass incarceration that now plague our society, a movement so crippling that today Black men have a one in three chance of spending time behind bars. This country was founded on the requirement of a second-class, an undercaste as she calls it, to keep the economy going. First slavery, then convict leasing, then Jim Crow, and the latest iteration? Mass incarceration. Ms. Alexander details a media campaign initiated under the Reagan administration that targeted Blacks in the new War on Drugs and revitalized a previously exploited the little clause buried within the thirteenth amendment: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” These were the images I saw on TV as I passed through the kitchen. I saw dark violence. I saw cops having a hard time keeping people in line. It seemed really rough out there. Poet and media activist Malkia Cyril explains in the film “13th” that white people aren’t the only ones to view Black men as criminals. It broke my heart as she said, “Let me be clear...Black people also believe this...and are terrified...of our own selves.” Two years ago, while one of my sons rode the bus to his summer camp, a mixed race child put my son in a playful choke hold and declared that “black is bad!” The boy’s grandmother was livid when I relayed the story to her, furious that her grandson had already been taught the false message that “black is bad.” It was a disheartening wake up call for both of us to say the least. Not only does Ms. Alexander point out the danger of mandatory minimums in jail sentencing (as well as the brutal nature of Three Strikes laws or charges for first-time offenders), in addition to the reality that Blacks are targeted for their drug possession at rates disproportionate to their drug use while cops turn their eyes from white drug crime, she details the lasting effects of holding a criminal record -- the loss of civil rights under a system that makes discrimination completely legal. Under this system, millions of people have lost their right to vote...or get a job...or maintain housing...or get an educational loan...or receive food stamps. Even when punishment is warranted, she says, these criminals are perpetual outcasts and have no way of redeeming their rights of citizenship after they pay their debt to society. You may have trouble reading her book. It’s incredibly damning and may make you feel defensive. If you want the highlights, watch the movie “13th” on Netflix. Her book is similarly focused on presidential campaigns and administrations. Reality is more complicated than that, and if you want a detailed approach to how the War on Drugs played out in a specific city, check out the history of Washington, D.C. in Locking Up Own Own by James Forman, Jr. If you find Ms. Alexander’s conspiracy theory of the CIA buying drugs and making a profit selling them to impoverished Black neighborhoods in order to win a covert war in Honduras, consider pairing the theory with a reading of The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (or just check out the film, especially the scene in which the protagonist’s father challenges her to consider how drugs ended up in the Black neighborhoods to begin with). If you feel no sympathy for those who can’t pay the rent, consider reading Evicted by Matthew Desmond. If you feel there is no way you could be considered a racist, consider reading Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People by Mahzarin R. Banaji. And if you want to believe in Bryan Stevenson’s message that “the opposite of criminalization is humanization,” read his book Just Mercy (or again, simply watch the film), and then fill your mind with images of Black people radiating hope (Becoming) and brilliance (Hidden Figures). Black literature is not all Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. We do not want to sweep history under the rug. The movie “13th” ends with images of Black men being shot in the street, or suffocated. These images are our reality. But as the credits roll, images of youth and achievement and love fill the screen -- all of the images of the scrapbooks you hope to make for your own children. We need to elevate Black Americans from their second class status and give them a place at the table that they have never seen in this country. While the exceptions of Barack Obama and Oprah Winfrey and Will Smith make us think otherwise, we cannot continue to renounce generations of men and women to the status of criminal. I don’t want my children to see Black as other or criminal. As a small start, we continue to read books like The Day You Begin, but we also read Peeny Butter Fudge, A Feast for 10, and Counting on Katherine. And we continue to open our eyes and ears to discern how else we can help. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|