|

Dear Friend, I was thrilled to see your name in my inbox, but it saddened me to learn your news. The more I hear updates from friends lately, the more I wonder if we are coming to an age where things begin to fall apart. This past May, I felt so depressed. Perhaps it was the rain. Or perhaps it was the grief I felt while reflecting on all of the brokenness around me. I’m so sorry for the loss of your grandfather. And for your uncle’s passing. I’m sorry to hear about your parents’ continued struggle through cancer treatment I’m glad you can be with your parents separately even as they finalize their divorce. I was shocked to learn about your husband’s cancer diagnosis. I am so sorry to hear about your divorce, and the worries you have about how it will affect your children. I cried out to God to bless you with a child when you battled infertility. My heart ached when you lost your baby. Later, I didn’t expect that your twins would be born premature when their father was in jail. Or that when you finally had your baby that you would have to watch him suffer through illness after illness. Or that he would need emergency surgery after the accident. Or that when you finally adopted your child you would learn that she needed extensive medical care. Or that after trying to treat a confusing series of illnesses you would be told that your child had a rare genetic disease for which gene therapy was still, at best, decades in the making. I never expected you would have to bury your child. I know it’s not supposed to be this way. I know God didn’t intend it to be this way. And I know it won’t always be like this. But right now, I am sorry for your loss, and for your pain. I know it won’t always hurt like this, that God is supposed to, one day, wipe every tear from your eye. During Easter service two years ago, our congregation watched a short video of one of our pastors arranging colorful, glass fragments onto a background we couldn’t yet see fully. With the camera lens zoomed in on his hands as he worked, the glass shards looked threatening, like they might slice his fingers. As music played throughout the construction, we wondered how the pieces would fit together. At the end, with the placement of the last piece, the artwork was raised from its working surface, and we gazed upon the finished product -- a wooden cross, embedded with those colorful shards of glass, and a human shadow illuminated from behind. This reminded me of Christ’s love, his sacrifice, his act of being broken in order to suffer for our brokenness. At times since then, our congregation sings a song called “Hosanna”. It reminds us that God grieves with us and loves us in our broken state. And we respond: Break my heart for what breaks Yours Everything I am For Your kingdom’s cause As I walk from earth into eternity My heart is breaking for you. For all of us. I am not a stranger to this pain -- to the diagnosis, to the accident, to the news that changes everything. When can I see you? I’ll hand you a glass of champagne. And we’ll sit together, here, at the bottom of the mess. All my love, Caroline P.S. These stories are a composite of the pain and suffering of many. They remind me that no one is untouched by grief. And also, that no one need be alone in their suffering either.

0 Comments

Earlier this month I visited the Broad Institute for the first time. I dug out a rarely-used pair of heels, rode the Red Line to Kendall and prepared to smile through a meet and greet. Attendees like me settled their nerves with a glass of wine or soft drink from the bar and tried to take cues from each other. Our hosts encouraged us to mingle. This was an event to bridge gaps between scientific minds and families, to gather up a variety of intellectual powers and band together for a cause our host described as “bittersweet”. Two years ago, our neighbors lost their first born daughter Sajni to diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a fatal brain cancer. While struggling through their grief, they threw themselves into pursuing doctors and researchers who might be able to crack this disease and bring hope to other children and their families. When the Broad Institute agreed to take on the challenge of investigating whether known FDA-approved drugs could have a role in arresting this disease process, our friend, Prabal Chakrabarti and his wife Vanessa were overwhelmed by the hint of promise. Prabal described it as “bittersweet… Bitter because it came too late for Sajni, but sweet because it’s going to help other children and other families.” (Quote from Boston Globe article “This Cambridge nonprofit is seeking every drug ever developed”. Click on this link to read the full article by Jonathan Saltzman.) This summer we celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Apollo 11 and man’s first steps on the moon. Neil Armstrong lost his daughter “Muffy” to DIPG in 1962. Was it his grief that spurred him on to greatness? It’s unclear. But I am similarly in awe of my friends who persevered to birth this research study at the Broad in order to bring hope to families, even if it is too late for their own. Once all of the attendees were seated for a formal presentation, I listened to President and Founding Director Eric Lander reminisce about the time when he and his colleagues sat around dreaming of the day they would sequence the human genome. He proceeded to list other examples of how their hard work transformed ideas that seemed akin to science fiction into realities that improved lives. Following his introduction, I sat enthralled as Drs. Todd Golub and Mariella Filbin detailed their plan to take every single drug known to man and attack cell lines from biopsies of patients with DIPG in an unprecedented attempt to identify a treatment for this vicious, inoperable and incurable pediatric disease. I wasn’t the only one inspired. “How much money do you need?” An eager audience member called out. “We’re looking at about $800,000 to complete this first phase,” Dr. Golub replied. After pondering that for a few minutes another audience member raised a tentative hand, “What can you do with $1.5?” The entire room dreamed for a moment. What could they do with $1.5 million? These were the people who sequenced the human genome. These were the people who cared enough to see this project through. These were the people to support. And why do this work? Please, as my recommended reading to you this month, read Prabal’s article from the Ideas section of the Boston Globe, linked here: https://www.bostonglobe.com/…/p6RsaUEyBtzAppjDOU…/story.html). Let your heart break with this family. Let your eyes cry tears of joy for the love they have found through their grief. Let your mind dream of what they might accomplish in the future. Then, click this link (https://giving.broadinstitute.org/searching-treatments) to learn more about the project. Think of what you can give. And double it. Click here (https://friends.broadinstitute.org/) and choose the designation “Sajni Chakrabarti Fund for DIPG Research.” Don’t let another fifty years pass without a cure. Every bit helps. Be a part of the community with us.

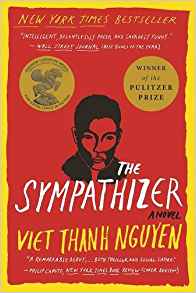

This 2016 Pulitzer Prize Winner for Fiction is dense, tense and astonishing. I worked hard to focus on each word. Each sentence was pumped with nuance and meaning. However, I think there were other reasons why I found the reading hard-going and why I found myself a little distracted. I recently started a writing class on the craft of memoir. I have wanted to be a writer for as long as I can remember. I always thought I would write novels, but I found that everything I had to say was a story from my own life. Perhaps I could just change the names and call it a novel? The jury is still out on that one, but the idea swirled around in mind as I read Viet Thanh Nguyen’s story, as well as an interview with the author included following the text. In his acknowledgements, Nguyen confesses that most of the story is true, although he states that he took “liberties with details and chronology” (383). Based on what I’ve learned so far in my class at GrubStreet, to me, Nguyen’s novel read like a memoir. I was fascinated to find the characteristics of memoir buried within a novel, so I spent almost as much time analyzing the structure of the text as I did reading it. Was this a memoir -- and whose memoir was it? At the start of each of my classes, my instructor introduces a necessary component of memoir. We have discussed what makes a good memoir. We have defined narrative voice and central inquiry. And we have studied forms of structure. And as I read Nguyen’s book, I reflected on each of those parts of the craft. The unnamed narrator (“Captain”) demonstrates a strong narrative voice which he uses to reflect on what he knew then and what he has learned since. However, the text is extremely compressed and fast-paced (not to mention heavy, violent and graphic), and I found myself begging the narrator to slow down and give me a little room to breathe. When we studied structure, I learned that, in addition to a rising action developed in the plot, a good memoir will also demonstrate a rising tension and simultaneous descent into meaning as the narrator searches for answers to the questions he has about his past. In the Captain’s case, questions about his origin, his parents, his “blood brothers”, his nostalgia for his homeland and his place in the revolution that Americans call the Vietnam War. But is there a rising action in the plot? When we read Tim Bascom’s essay “Picturing the Personal Essay: A Visual Guide”, I considered that Nguyen might be using what Bascom calls the “whorl of reflection”, in which writers “meander around their subject until arriving, often to the side of what was expected.” He concludes that “we don’t read an essay like his out of plot-driven suspense so much as for the pleasure of being surprised, again and again, by new perspective and new insight.” Now, Nguyen’s plot isn’t lacking for suspense! Dramatic escapes during the fall of Saigon? Covert missions plotted on American soil? An insider’s look at the filming of a movie very akin to Apocalypse Now? A second attempt to overcome the Vietcong only to be imprisoned in a re-education camp? But this is the Vietnam War -- or, as the Vietnamese call it, the American War -- and we know this book won’t culminate in a dramatic and decisive battle the way we think of D-Day bringing an end to WWII. So what is the narrator searching for? In class, we learned that a memoir’s tension is woven through the text by a central inquiry. My teacher said he heard a professor once claim that most memoirists struggled to answer two questions: “How did I get this way? And how do I stop it?” We learn from page one that the narrator is a spy. As reader, we wonder how he ended up in the role of a mole and how he is going to be found out. We wonder what he truly believes and which side he will end up taking. After 307 pages of powerful prose, the reader is slammed out of the memoir and into the novel that of course, this awarding-winning fictional piece was all along. Unfortunately, with that twist, I lost interest a little. The spell had been broken. As one of my former library book club leaders liked to say, “discussion illuminates”, and fortunately, the day after I finished reading this book, I met with my fellow library book club members to discuss it. After commiserating about the way Nguyen portrays women in the book (a book of the times...or did he go too far?), we spent time hashing out the ending and analyzing whether Nguyen wanted to make a statement about Vietnamese people or the Vietnam/American War or both. By the end of the evening I believed that, true to Bascom’s “whorl of reflection” idea, the narrator ends up “to the side of what was expected.” In an interview with Paul Tran, included at the end of the text, Nguyen comments, “I want readers to be rattled by the book. That might be the most I can hope for the book politically...I want this book to provoke people to rethink their assumptions about this history, and also about the literature they’ve encountered before…” (Asian American Writers’ Workshop’s The Margins, June 29, 2015). On the fortieth anniversary of Black April, the fall of Saigon, Nguyen published an essay in the New York Times Sunday Review Opinion pages (April 24, 2015). After sharing his own family’s story of escape to the United States and the lives they have led since, he zooms out to look at the impact of not only the Vietnam War but also the wars in the Philippines and in Korea which likewise brought many refugees to American shores. “We can argue about the causes for these wars and the apportioning of blame, but the face is that war begins, and ends, over here, with the support of citizens for the war machine, with the arrival of frightened refugees fleeing wars we have instigated. Telling these kinds of stories, or learning to read, see and hear family stories as war stories, is an important way to treat the disorder of our military-industrial complex. For rather than being disturbed by the idea that war is hell, this complex thrives on it.” After reading all of this, my book club concluded that at its heart, Nguyen’s book is an “anti-war” book. He leaves us with many questions and prompts us to seek out the many Vietnamese voices, as well as voices from other minority cultures, that until now have only received non-speaking roles in our movies, and in our society.

This book is a challenge, but I know you’re up to it. Whether you walk away fuming...or whether you walk away thinking this is the “best book you’ve ever read” (one of my mom’s friends thought that), you won’t be sorry you gave it a chance. I’m going to try to soak up what I’ve learned and let it improve my own writing. And perhaps, after we marinate in the juices long enough, the book’s greater messages will soak into the fabric of our society as well so that we can all enjoy a new richness and a new understanding of each other. While driving my son to his piano lesson the other morning in a nearby community I noticed a series of signs decorating the median advertising a bike drive at a local church. Maybe they’d have a new bike for my daughter! I loved the idea of grabbing a second hand bike and avoiding sticker shock at the bike store. I decided we would check it out after the piano lesson.

The bike drive was being held just a few blocks away. After his piano lesson I told my son my plan. We left our car in the parking lot and began our walk over to the church. As we rounded the corner onto the correct street I caught glimpses of houses I had never seen before, tucked away behind tall privacy fences. These houses were magnificent, spacious even, with neatly manicured lawns. Almost little castles. They definitely qualified as estates, especially if you could block out the fact that the lots were so small they nearly sat one on top of another as the size of these mini mansions dwarfed their surroundings. Even so, their lawns were about ten times the measly patch of dirt that comprised my front yard. Coveting property doesn’t hit me too often, but I wanted one of those houses. My son and I continued on and found the bike drive pretty quickly. A team of about ten or fifteen junior high and high school aged boys was working on a similar number of bicycles. With wrenches cranking and bike pumps inflating tires, they seemed off to a productive start already. The kids themselves looked a bit sleepy, perhaps there a little begrudgingly, and I was struck simultaneously by the feeling that I had been mistaken about this whole event. “Hey there,” I called out, “Are you guys selling bikes today or just collecting them?” “Just collecting them,” the boy closest to me replied. “Oh, all right,” I tried to keep my voice light, “Well, it looks like you’re off to a good start already. Good luck!” “Thanks,” he mumbled. I took my son’s hand and led him away, admitting to him that I’d been wrong about the drive, that they weren’t selling bikes so we should just return to our car and head home. My son accepted the change in plans easily enough, happy to skip along and babble on about his upcoming birthday, while I was left just a little shaken, a little embarrassed. I was upset because I felt like somehow I had ended up on the wrong side of a different kind of privacy fence. I had grown up in a community like this one, where everyone had a contract with a landscaping crew to maintain their perfect lawn. Shouldn’t my family be here now? Shouldn’t my kids be the ones (like these pouty pre-teens) collecting the bicycles and providing them to those who were really in need? Why did I suddenly feel like a beggar, hoping to get a used bike for my daughter and save some cash? On the walk back to the car I struggled to hear my son’s voice over the whoosh of cars rushing by on the busy boulevard, and as I glanced one last time at the beautiful homes I tried to convince myself that I wouldn’t want to live there anyway. No wonder they needed high fences -- they weren’t just for privacy but also for buffering the traffic noise. Consistent with my tendency to let things snowball in my mind, I began second guessing several recent choices, starting with taking my kids to get school breakfast the day before. School breakfast is now free to all students in the Cambridge Public Schools. Someone suggested to me recently that this was a bad policy, that the policy allowed parents to abdicate their role of feeding their children. But the school cafeteria had advertised special Friday breakfasts this month, and my kids were very excited about this week’s option. Should I have denied them the opportunity to have school breakfast because we could afford to have our meal at home? Was I taking advantage of the system by allowing them to take the free breakfast? Should I have tried to pay for it? I have written previously on this blog about the monthly markets at many of the Cambridge Public Schools. Food For Free provides a variety of produce, dairy, meat and non-perishable items for the school communities. The markets are open to everyone -- parents, teachers and staff members make their way to the cafeteria each month to partake of this event. When my kids’ school began to host a monthly market this school year I decided I wanted to help out. Since the fall I have volunteered to help unbox and arrange the food on cafeteria tables in order to prepare of market opening. And once we’re all set up and ready to go, I shop early in order to get my selection of food in the trunk of my car before heading back into the school to gather my children. This food has helped me out on more than one occasion -- like the time I had forgotten to stock up on peanut butter. It has given me ideas on what to cook based on the produce available. It has pushed me to offer my kids more fruits and vegetables than I otherwise would. Knowing that my kids often refuse to eat them, I realized that I had grown in the habit of skipping vegetables more often than not, or at least not offering anything more adventurous than frozen mixed veggies from a bag. Still, for the first few months of the market’s existence at our school, other moms would whisper in my ear, “Do you think it’s okay if I shop? I mean, I can afford to buy my own groceries. I don’t want to take food away from someone who really needs it.” I had similar concerns at the beginning. I asked the coordinator’s advice. She reassured me that the market was open to everyone and that there was often food left over that she tried to ferry to another location for distribution. I passed along this feedback to my friends and added one point of my own: that if everyone participated then more people would feel comfortable attending. Most people have that pride that makes it uncomfortable to admit they can’t make ends meet on their own. I wouldn’t want the market to exacerbate any visibility between the haves and have-nots. I thought of the market as my son and I retrieved our car from the parking lot at the music school, and I considered where I wanted to be on the scale of having or not having. I realized that I had assumed growing up that the goal would be to end up at the top of that continuum, whereby ensuring my family always had more than we needed, we could be free to act as saviors to those around us. We could serve and hand out help and feel good about ourselves. It made me uncomfortable to accept that wasn’t my reality. And yet...was it really a goal to strive for? Four years ago when my twins were born, friends and neighbors delivered meals to my family daily for three months straight. Did we really need the food? No. Could we have afforded take out? Yes. So how could I have accepted the handouts that these families delivered so sacrificially? Because I needed something other than food. I needed to feel not alone in this, my struggle to figure out that transition. About a year or so after that, at school pick up, several tiny people were screaming at me for something to drink, and I was empty handed. The mom next to me in the pick up line -- the mom who spoke English as a second language, who drove for Uber, who had a history of marital abuse that ended in divorce, a mom who I would have labeled as far needier than me -- bent down to fish out a smoothie from her purse and a juice box from her own daughter’s lunchbox. She thrust them in my hands and insisted I take them. I swallowed my pride in that moment and took them from her. I didn’t want to be the one in need of help, but who was I kidding? I was a young woman with disheveled hair juggling four kids, two in a stroller but all four wanting to be held. I looked like I needed help. And who was I to refuse this other mom and risk offending her? That moment brought the two of us closer, and as I drove away from the piano school recently I remembered the lesson of that time. You could say that neighbors helping neighbors is a far cry from blanket services that ensure daily meals to all school children or, beyond that, services in place to help anyone we think should be able to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and help themselves. But then I think of every time I have been able to relax and enjoy my family or a community event because dinner has been provided. Once a month I drop off a sandwich dinner on behalf of Community Cooks to a group of elementary kids. Am I enabling their mothers to abdicate responsibility for preparing dinner? No, I like to think I’m gifting them with an evening of not having to decide what to feed their families (anyone else struggle with meal planning?), although it possibly could go further than that and save them from making the choice between feeding their families or keeping the lights on. Regardless, we could all use an evening off from our worries. And, on a larger scale, I remember a friend who upon returning from medical missions in Africa said the people there were thankful for the money and medical care we send...but that they keep us in their prayers as they learn about America’s struggle with depression and suicide. Do we need their prayers any less than they need our funds? I try to be self-sufficient. I try to take care of myself and my kids. But there have been both long periods of time and many small moments when I haven’t been enough. And there will be times in the future when I need help. My goal is not to seek the top where I can sit and act as savior. It’s an illusion anyway. How much better to be in the community where we can take turns washing each others’ feet? Sure, most of the time I don’t want to expose my inadequacies. But I am glad that I am not an island. Because once we are through the difficult times and back on our feet, we are able to serve once again, this time with a tighter, stronger community around us. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|

||||||||