|

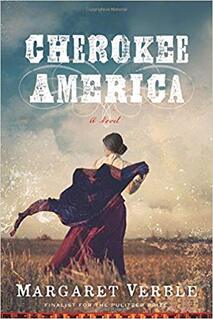

This month, my library book club tackled Margaret Verble’s dense feat Cherokee America, a tremendous work of historical fiction that vividly illustrates the life of a mixed Cherokee-white woman named Cherokee America Singer, known to her community as Aunt Check. Born to a white father and Cherokee mother and raised in Ohio and Tennessee, Check struggles with the emotional separation she feels from her people, not having walked the Trail of Tears with her tribe.

The events of the novel take place during the spring of 1875, yet encompass sweeping issues of race, class and culture that live on today. At times, readers in my book club admitted that they felt like they were reading a modern story or at least that they couldn’t place Verble’s tale in time. I felt the same way...when the black hired hand is wrongly accused of murder...when the Cherokee work to great lengths to prevent U.S. marshalls from invading with their own laws. And I compared this book to other related narratives and histories I have read in recent years. Verble’s work complicated my view of the Osage tribe that I grew to hold after reading Killers of the Flower Moon, and her work affirmed the complexity of the issues involved in post-Civil War America that were illuminated in Reconstruction: A Concise History. About a year ago, my husband and I visited the Hermitage, the plantation outside of Nashville where President Andrew Jackson retired. We talked quietly as we toured the grounds, observing the solemn tone, especially when we came close to and entered slave quarters. We read plaques that described the ban on certain types of music, saw pictures of the instruments the slaves would play illegally. I commented to my husband that ironically, I had just looked at toy versions of those same instruments in catalogs I perused while compiling Christmas lists. Our culture still has a long way to go, but this was one small example of how it’s becoming more mainstream to embrace different cultures rather than force assimilation. As we rounded the path that would take us back towards the mansion, we were struck by the sight of a small white sea in front of us. Indistinct at that distance, I squinted and asked, Then I picked it. I picked a large handful and stuffed it in my purse to bring back to show my children at home. I did it quickly because I severely doubted I was allowed to take a sample. But I wanted it. I wanted to feel this history, and I wanted to celebrate what could have been.

Seeing the brilliance of the cotton made me wish I could erase the stain on our country, the stain of exploitation and brutality. But since that isn’t possible, I am glad for writers like Margaret Verble who add their characters to our catalog of American experience. Because, as one reader said at another book club a few years ago, “We’re still here,” meaning that she and other Native Americans are still here, many with voices yet to be heard. Whether your community celebrated Columbus Day or Indigenous People’s Day recently, consider picking up Verble’s work or another work by a native writer and enrich your culture with a complexity that breeds truth and connection.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|