|

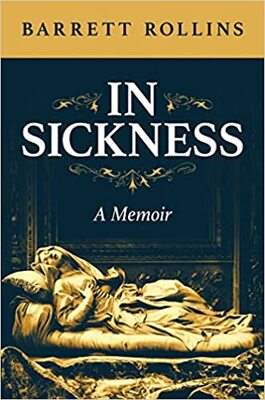

During my first month as a doctor, one of my elderly hospital patients refused my recommendation to schedule a colonoscopy. I had conducted a small bedside test that indicated she had blood in her stool. It was standard procedure, I explained, to then find the source of the bleeding, and most importantly, rule out colon cancer. “No,” she said softly but firmly with her husband next to her, equally resolute. She’d been through enough. No more workup. She refused my senior resident. She refused my attending physician. She became the subject of debate. How much to push her while she was still in our midst, receiving care for another issue? Everything we had taught ourselves said that she needed this test. But what if our assumptions were wrong? In the middle of this crisis of conscience – which might have lasted one day or three, I can’t remember – I had an epiphany: I had read my test result wrong. Everyone who has taken a COVID test by now knows that there is a line that appears for “control” and a line that appears for “test.” Her “control” line had been positive, I realized, not her “test.” In my first-time-as-a-doctor nervousness, I had invented a problem. By the end of my intern year – really by the middle, after a winter of calling time of death on multiple people each time I was on call – I had changed my tune from “workup at all costs” to telling my husband that if they asked him for my advanced directives, please let any hospital personnel know that I was “do not resuscitate,” “do not intubate,” “do not hospitalize,” and “do not touch under any circumstances let me die in peace thank you.” Because was death, especially in this 80-something-year-old woman, really the worst thing? After reading Dr. Jane Weeks’s story first in the Boston Globe and later in her husband Dr. Barrett Rollins’s memoir In Sickness, it seems like the renowned Boston oncologist and researcher would have agreed with me – that patients should be empowered to be able to make a clear-eyed choice regarding medical and end-of-life care, and to even be able to decline it, especially weighing the toxicities of certain treatments, like chemotherapies.

Indeed, in real life, she largely refused treatment for her own breast cancer, which she diagnosed in herself about ten years before her death, kept secret for six years, and only confided in her husband when she thought she was dying. For the last four years of her life, she bound him to her secret, refusing to let him speak of it to anyone.

This is another layer to the mystery: Not only does Weeks make us question how treatment conversations should take place between doctor and patient, she also demands we consider who has a right to know our medical history to begin with. Was she wrong to refuse treatment for breast cancer? Was she wrong to force her husband to keep her secret? And was her husband wrong in keeping the secret from everyone else? When the news finally leaked that she had end-stage breast cancer, concerned family members and colleagues who yearned to be close to the fierce woman they long admired as a mentor and physician researcher wanted to do something to help her. And the reader presumes that these family and friends would have wanted to know what was going on with her. This month, ten years after his wife’s death, Dr. Barrett Rollins lays it out for everyone in his scene-driven story about his wife’s struggle with breast cancer. The memoir opens with her near-death experience that landed her in the ICU and from there, chronicles her last year of life and her husband’s caretaking role during that time. By the end, we definitely know what happened, but we are no closer to understanding why, or whether the writer thinks it should have happened this way or what the alternatives might have been. I expected this memoir to delve deeper into Dr. Weeks’s research and arguments, or at least some greater exploration of her past that created her intense phobias and personality. I thought such a discussion would be worthy of attention and could be used to try to improve communication between doctors and patients, especially regarding end-of-life issues. Then again, this wasn’t her memoir; it is her husband’s, but the thing is, while he is present on every page, we learn so little about him that I don’t think it can be called his memoir either. He includes a few lines about his intense reluctance to face conflict and the turmoil he experienced as he considered several times whether to break his vow of secrecy. Still, in the end, it avoids any deep reflection regarding their marriage or the role of sharing medical news. By the end, I couldn’t see this as anything more than an attempt to absolve her of any requirement to seek medical care or share her medical condition, and to absolve the writer of any complicity in the outcomes. Did they have love in their marriage? Yes, he argues. Did they support each other? He supported her every day of her life. This book could have been titled, “In Defense of My Actions,” and yet, perhaps he chose “In Sickness” in order to argue that no one can know the nuance of a marriage from outside of it. Theirs was a particular relationship, he argues, that in revealing the story on these pages, he hopes to explain to the world. I’m not sure if Jane Weeks' life and death will have an effect on the practice of healthcare or oncology or the research of either, but for those who are aware, perhaps we might individually reflect on our motives for seeking medical care or not. For anyone seeking eternal life, I still strongly recommend religion. For my friend, Grace Segran, who sought treatment for her breast cancer, chemotherapy deprived her of enjoying her life, and she chose hospice in the end. For myself, I recently waited through almost four weeks of congestion, coughing and sinus pain, only going in for treatment when my kids fell sick. I might wish to never step foot in a medical office again, but how could I knowingly spread germs to them? For them, I took my antibiotics and steroids and began once again to sleep at night. We can’t know Jane Weeks’ motives completely, but we can hope that she lived tenaciously, purposefully, and in accordance with her own wishes, to the very end of her truncated life.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|