What with so many normal points of connection suddenly severed, I clung to my friend’s book recommendation like a little lifeline. It reminded me that the top reason I love reading so much is that it connects me to others. If I wanted to just read a lot of books, I could sit in my living room and devour mysteries or romances, but it wouldn’t help me consider what my friends and neighbors were thinking about, or what they were wrestling with. Most of the books on this blog were recommended to me, and it means so much to me that as I scroll through my reading lists, the titles I see prompt me to remember the names of people I know.

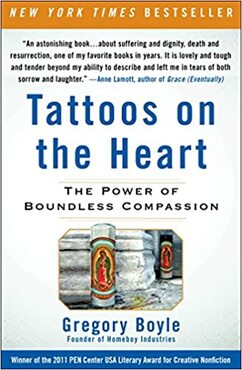

So when I picked up Jesuit Priest Gregory Boyle’s book, I didn’t worry about what type it was. My friend told me it was “so good”, and that was good enough for me. Yet, in his preface, Boyle seems fixated on trying to skirt any definition of genre. He mentions some of the things that this book isn’t, saying it’s not a memoir or a how-to on dealing with gangs. He points out that there is no narrative chronology. He didn’t intend to write a sociological study or even a call to action. But as I turned the pages and fell more and more in love with Boyle’s stories, it became quickly apparent what this book is. This book is permission to cry. When life, as it had been lately for me, demands that you put one foot in front of the other and keep tackling problems and continue to strive to do better, no matter the circumstances, this book gave me the space and reason to let it all out. In a nutshell, Boyle’s book is about L.A. gangs, grief, and Jesus. Gang culture is terrible, to bluntly understate the obvious, and like seeing Jesus standing over a deceased Lazarus, the reader, like Boyle, is at times drawn to indignant tears of why the heck haven’t we solved this problem yet? Why should a teen girl in his book need to specify that she should be buried in a sexy red dress (“Promise me, that I get buried in this dress”), expecting not to make it to middle, let alone old, age? (89) And how eye-opening is this view of teen pregnancy, when another teen comments: “I just want to have a kid before I die.” To which Boyle responds, “I’m thinking, How does a sixteen-year-old get off thinking that she won’t see eighteen? It is one of the explanations for teen pregnancies in the barrio. If you don’t believe you will reach eighteen, then you accelerate the whole process, and you become a mother well before you’re ready.” (90) In the midst of frequent violent death, Boyle muses, “Enough death and tragedy come your way, and who would blame you for wanting a new way to measure [success].” (177) Boyle finds that new way in Jesus, who reminds us that our purpose in life stems not from our success but from our faithfulness to love. As Boyle describes him: “Jesus was not a man for others. He was one with others. There is a world of difference in that. Jesus didn’t seek the rights of lepers. He touched the leper even before he got around to curing him. He didn’t champion the cause of the outcast. He was the outcast. He didn’t fight for improved conditions for the prisoner. He simply said, “I was in prison.” (172) Boyle points out that ““The Left screamed: “Don’t just stand there, do something.” And the Right maintained: “Don’t stand with those folks at all.”” And yet, “[t]he strategy of Jesus is not centered in taking the right stand on issues, but rather in standing in the right place -- with the outcast and those relegated to the margins.” (172, bold italics mine) Boyle tries to do this in his gang-dense neighborhood in L.A. He founds a work program called Homeboy Industries to help funnel gang members off of the streets and into employment, and in doing so, opens his life to theirs. It seems natural, this interaction of priest and gang member, this intersection of love and recklessness. So when Boyle is overcome with grief at one boy’s funeral, the reader cries in solidarity. And when, in the same moment, a bystander scoffs at Boyle for crying, letting him know he thinks the deceased was not worth another thought, the reader too feels the punch in the gut as the world rears its ugly head and forces its own expectations, marching effortlessly over love and mercy, leaving them crushed in its wake. As Boyle stands there wondering what to do, he remembers that “[b]y casting our lot with the gang member, we hasten the demise of demonizing. All Jesus asks is, “Where are you standing?” And after chilling defeat and soul-numbing failure, He asks again, “Are you still standing there?” / Can we stay faithful and persistent in our fidelity even when things seem not to succeed? I suppose Jesus could have chosen a strategy that worked better (evidenced-based outcomes) -- that didn’t end in the Cross -- but he couldn’t find a strategy more soaked with fidelity than the one he embraced.” (173) Boyle reiterates this point over and over again, that “[s]uccess and failure, ultimately, have little to do with living the gospel. Jesus just stood with the outcasts until they were welcomed or until he was crucified -- whichever came first.” (172) After burying nearly hundreds of gang members whom he came to love, Boyle acknowledges that the world might not give us the permission to grieve the way we need to in order to heal. Reading his book, I grieved for the lives lost in L.A., and I grieved for everything else wrong in the pandemic and in our lives as well. It was hard to stop crying actually. And yet now I think, what better way, in fact, to let each other know, you were loved? These lives, as Boyle’s example shows, are worth our tears.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|