|

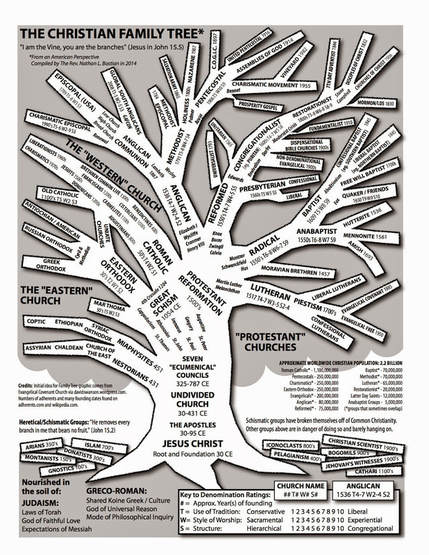

My friend asked me this. Over email. And continued, “does it mean you try to convert people?” I stared at the computer screen for a few moments, wondering what she already knew and believed, what she wanted to know, and what kind of answer I could possibly provide her. Would my reply jive with my church’s official definition? Would it meet my Evangelical friends’ approval? I felt a sudden chill and a gut-wrenching feeling of responsibility to give a brighter face to a word that has grown so tainted. And then I told myself to get over it, to answer her question honestly from my own experience and then later conduct massive internet research as well as quiz my Evangelical friends about what they would say. I wrote her back within minutes of reading her email. This is what I said: “I really admire your open curiosity. I will get to work on a piece to answer your question on evangelicalism. I know you aren't the only person who wonders that. In a nutshell, Jesus called Christians to share the gospel and love others. The conversion piece gets muddled because of that great commission. There have been a wide variety of ways people have interpreted the call to share the gospel -- anything from blatant war to faithful service like that of Mother Teresa. I believe the Bible says only God can convert hearts, but that Christians are supposed to have a positive influence by living out their faith.” A few days later I told her in person that I had spent some time fleshing out my answer to her question and that it was taking a turn into trying to also answer the question, “What is a Christian?” My friend suggested that different Christians would answer these questions in as many ways since there are so many branches to Christianity. Beneath those comments I felt another unspoken question: “How can I believe anything anyone says when Christians can’t even agree among themselves?” After that conversation I felt completely deflated. What authority could I possibly have to answer anyone? Should I even attempt to answer these questions? Yes, I decided. Even if only for myself. I was going to work through this. Speaking to my friend reminded me of another conversation I had earlier this year, just before Easter. While at a playspace near my house I ran into a neighborhood mom I only know in a cursory sense. She was there with her young daughter and new baby. I was there with my four kids. While our mobile children constructed obstacle courses and forts out of foam mats we made a fuss over her baby and shared updates from our lives. I was anxiously anticipating having all four of my kids in school, a reality still over five months away, but was keeping busy in the meantime organizing events and discussions for moms and families in the neighborhood. She shared that she had recently returned to part time work and was now in charge of events for a branch of the Jewish Community Center. We talked about the ins and outs of project planning, and she felt compelled to share that she was secular Jewish, and that these events are open to everyone. I shared that while I help run a Christian after school club for my kids and classmates of theirs, which is open to everyone as well, it isn’t always perceived as being inclusive. “Oh, you go to church?” she asked, surprised. “Yeah,” I said. “I mean, I know there are churches around here but, well, not those churches, but you know, other ones.” She waffled, landing on the safe local assumption that the churches around here must be okay because this is the land of the tolerant and okay. “We go to an Evangelical Church,” I clarified, not wanting to call her out but not wanting to hide either. Pause. Her mouth opened. She waited. “Oh. I didn’t know there were churches like that around here.” “There aren’t many. There are three main ones. We go to one in Arlington.” I swallowed, considering what to say, what she might want to know. “It’s not political. It’s just about people trying to live out their faith.” She nodded, and I could see her wondering if we were still meant to be friends, perhaps wondering if she should still consider me a sane person. But then she said, “I was going to take my daughter to an Easter egg hunt this weekend because Easter is coming up,” she smiled weakly with a glance at me, “but I guess you know that. And I was trying to tell her that Easter isn’t really about the Easter Bunny and eggs but then I couldn’t remember what it really was about. It’s not Jesus’ birthday, right? That’s--” “That’s Christmas,” I supplied. “Christmas. Right. But it’s…” She trailed off. “Good Friday is when we remember Jesus’s death, and Easter Sunday is when we celebrate his resurrection.” She nodded but there wasn’t much recognition on her part and as she wondered aloud why Easter coincides with Passover we were interrupted by the need to rescue a child from a collapsing foam tower. Our time moved on, but I continued to mull things over. I found myself coming to a slow understanding of how she could have grown up in this country and have little knowledge of the Christian story. Over the past forty or fifty years Americans have worked tirelessly to brush Christianity out of schools, and some who wish it gone have told me personally that the work is far from finished. How does this affect us? At my children’s school families are invited to present on a holiday and share family traditions. The Christians I know don’t dare present on Christmas or Easter for fear of offending someone. Christianity began as a cult following and is once again a taboo religion. Unless you seek it out you aren’t likely to learn the Christian story. I worry that in the absence of education Christianity has been reinvented as loud extremist voices and antagonistic political views. Later that evening I emailed my neighbor the following information: “Easter coincides with Passover because Christian believe Jesus is the ultimate sacrificial lamb, that his death was the fulfillment of the Jewish law to take away the penalty for sin forever...but that the death wasn't the full story because as he rose again, Christians also believe they can rise to new life to be with God forever (which some call Heaven) when they choose to follow Jesus. That's the faith in a nutshell! The eggs and baby animals in commercial Easter I think just serve to symbolize new life. Who knows where the bunny comes in.” In reply, she thanked me for the information, went on to describe Passover itself and noted how interesting how there was so much “overlap...with symbolism” in Christianity and Judaism. In the end, I was disappointed by this gap in knowledge, but I saw hope in my friend’s patience in learning something new and her desire to educate her daughter on the traditions of another faith. I have discovered many other mothers in the community who share similar hopes to raise their kids in a religious tradition as they seek to understand those around them. Our interfaith gathering this past spring helped us grow closer in that vein. One of the questions asked at the gathering was this: “Can those who are Christians here please explain which sect of Christianity you are affiliated with and how it compares to the others?”  http://natebostian.blogspot.com/2014/12/christianity-in-two-hours-or-less.html http://natebostian.blogspot.com/2014/12/christianity-in-two-hours-or-less.html As mothers boldly gave answers reflecting their personal experiences, I felt daunted by the bigger task of explaining it all. In the beginning, it was really very simple. Jesus gave a command called The Great Commission to go and share the gospel with people of all nations. People did that. And the church grew rapidly. But then something happened. As time moved on people interpreted Jesus’ command in different ways. The Christian Tree is now a dizzying spectacle of disagreement. Check out this example from Nate Bostian’s blog. I believe it’s the same diagram my church uses to talk about church division. As my pastor once suggested, when you tell someone what kind of church you attend they immediately place you somewhere on this tree. I’m not the only one bothered by what appears to be great division. Right here in Boston there is a small group of Christians called UniteBoston dedicated to reuniting the church by creating spaces for different congregations to share their experiences and gifts. As for me, I was raised in a Covenant and later an Evangelical Free Church, both north of Chicago. We didn’t discuss politics or current events at home, and the only national movement I heard about at church was the True Love Waits movement that encouraged waiting for sex until marriage. And now in this country the word evangelical is easily associated with all kinds of political movements that are generally considered antagonistic. Earlier this year yet another friend (number 3 for those counting) mused over email that: “Your typical religious Christian is conservative. Conservatism in this country is stereotypically anti gay, anti abortion, pro guns, anti immigrant, anti welfare.” She could spell it it out easily, as a simple description of the way things are. I have felt blindsided time and again over the past few years as I realized I never had a finger on the pulse of our country myself. When I read other people’s experiences with evangelicals, like in Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance and Faith Ed by Linda K. Wertheimer, I feel two things: first, like I’ve been living under a rock, and second, angry that there could be so much misunderstanding. The history of evangelicals in this country has affected me personally. In my discussions on my webpage on interfaith conversations I talk a little about my experience with sharing my faith in junior high and how that damaged friendships. In high school, with the invention and later widespread use of email, I found another outlet to write about my faith. For several months I regularly sent emails with short devotions to a broad list of friends from school. One friend politely asked to me removed from the list, describing himself as an atheist. Others thanked me for my writing, so I kept it up for awhile. College was a time of falling away from God, followed by a long time of seeking to return. While my husband and I had tried on and off to find a church where we could grow, it wasn’t until our second child was about to be born that we pursued the quest in earnest. We started attending Highrock in Arlington, MA in February, 2013 and came to consider it our church home. Highrock is an Evangelical Covenant Church. In my current community, friends and neighbors have shrunk away a little when I share that I attend an evangelical church. “And do you still think you belong there?” one friend (number 4) asked me last Christmas. “Yes,” I said, while thinking, I am an Evangelical. You can’t take it out of me. “Okay,” she said slowly, pursing her lips and trying to retain a sense of polite tolerance that common culture demands. I could sense her anxiously waiting to change the subject. I left that conversation feeling misunderstood and not accepted. For the record, my church’s denomination, the Evangelical Covenant Church, defines their identity this way: “We are united by Christ in a holy covenant of churches empowered by the Holy Spirit to obey the great commandments and the great commission: to love God with all our heart, soul, strength, and mind, to love our neighbors as ourselves, and to go into all the world and make disciples.” “To see God transforming every neighborhood and institution in Greater Boston through locally-focused congregations who live and love in such a compelling and Christ-like way that our neighbors are challenged to seriously consider the claims of Christ, be reconciled to God, engage in Christian community, and serve others in the unique ways God designed them to, so that Boston becomes a “city on a hill” that will be a blessing to the world.” So, you say, are you trying to convert people? I believe only God changes hearts, but we can and should take an active step in seeking Him. The Bible says, “Draw near to God and He will draw near to you.” -- James 4:8 As Christians, we are called to influence others by living out our faith:

So how does a Christian live and grow in the twenty-first century? I have found it helpful to: 1) return to the basics of Jesus’s teaching [Love’s Last Words series that begins with the sermon Father, Forgive Them], 2) ask the world to forgive us for the wrongs we have committed as a church [Forgive Us series beginning with the sermon Judgmental], and then 3) go and love others differently [BLESS series that begins with the sermon Exiles]. In the beginning, it was really very simple. Jesus gave a command called The Great Commission to go and share the gospel with people of all nations. People did that. And the church grew, rapidly. But then something happened. The church grew in power...and grew in corruption and abuses and offenses. Today, growing pockets of our country are left with a negative impression of the church. In a sermon from April of this year called Exiles, my pastor suggested that the church’s fall from grace could be a blessing in disguise. Instead of forcing others to see our views, instead of trying to "fix" others, and instead of just trying to "fit in", we can live differently. We can return to our first love; we can forgive ourselves and others; we can extend grace to those we disagree with; we can listen to those who have been hurt. And, if people want to know, we can share how following Jesus has made a difference in our lives. What does it mean to be an Evangelical? For me it means repeatedly being vulnerable with my friends. It means taking the risk to be different. As Christians, every day in fact, we have a new chance to practice the humility we preach and to offer grace-filled, steadfast serving love as we seek to follow Jesus’ example to love the world.

1 Comment

Cindy

10/15/2018 10:16:42 am

So well written. Some Christians have lost sight of our ultimate command to love. We are not called to judge but to be the face of Christ.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|