|

This summer, I’ve been sitting at a desk in an alcove that is flanked by bookshelves. I’ve been sampling the titles from those shelves, books that are now strewn about the desk along with my class assignments and essay research. There have been so many difficult stories, starting with two novels that featured selfish, albeit hurting, women who went to very questionable lengths to adopt a child (The Light Between Oceans by M.L. Stedman and Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng). Then there was the Italian WWII story, a novel based on the life of teenager Pino Lella from Milan who helps Jews escape over the Alps to Swizerland before working as a driver for a Nazi General while doubling as a spy for the Allies (Beneath a Scarlet Sky by Mark Sullivan). I considered picking up another Liane Moriarty book next in order to lighten the mood (The Hypnotist’s Love Story had been particularly entertaining back in July), when my eyes landed on a title that called to me, especially as I watched the news unfold out of Afghanistan.

As I watched President George W. Bush announce his intentions to invade Afghanistan, one of my roommates walked in, took one glance at the screen, and declared Bush the terrorist. I was confused. Weren’t we allowed to react? I thought of all of those people, the pictures I had seen of them falling from the towers and the replays I had listened to of the 911 calls from those trapped within them. I really wanted to understand what my friend was thinking, so I opened my mouth and asked something like, “But don’t all those people deserve to have their killers held accountable?” Instead of answering my question, my roommate yelled something and went to her room, slamming the door behind her, and leaving me in front of the TV with more questions than ever. I was shocked. If my friend wasn’t going to talk to me, how was I going to learn about what was going on? Looking back, this moment still pains me because it felt like such a significant example of and my first real experience with the assumption that presumed political alignments will preclude any discussion between different viewpoints. There I was, completely lost about what to make of anything, and the only thing I learned was that asking a question was rude and offensive. (And it was no surprise to me later that my alma mater Brown University was used as an example twice in Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s impressive book The Coddling of the American Mind, an example of a place where dissenting points of view were not welcome.) I’m glad I’ve since learned a bit about Islam and about the Middle East from reading books like If The Oceans Were Ink and Everything Sad is Untrue, both of which helped to flesh out the narrative of The Kite Runner when I finally picked it up last week, but I hoped to learn even more about the political conflict, something that would help me understand what was going on now, and what had happened that led to history repeating itself. While the beginning of my understanding of conflict in Afghanistan occurred in 2001, Khaled Hosseini’s character Amir in The Kite Runner, draws a different line in the sand: the bloodless overthrow of the monarchy and resulting formation of the Republic of Afghanistan on July 17, 1973: “The shootings and explosions had lasted less than an hour, but they had frightened us badly, because none of us had ever heard gunshots in the streets. They were foreign sounds to us then. The generation of Afghan children whose ears would know nothing but the sounds of bombs and gunfire was not yet born.” (36, bold italics mine) Hosseini’s story is largely a book about children, and the teenagers and aggressive young men some of them become. When I take a step back and look at the last fifty years, it appears that each generation of violent extremists are young people who hadn’t even been born when the previous upheaval happened, making me wonder how they learn this violence, and why they choose to repeat atrocious behavior? The Kite Runner is the story of Amir, a boy torn between his desire for two loves -- the love he wishes he had from his father, and the love of a boy who is like a brother and yet not allowed to be. Amir is raised breathing the racism that pervades the country. He adds to it in lesser ways than the neighborhood bullies, and yet, his inability to escape it alters the course of his life. Even after educating himself via an old textbook and learning the history of how his people oppressed the Hazaras, he has no one to turn to for guidance, for the truth of equality and friendship his conscience craves. His teachers preach racism, and his father permits the discriminatory classism that is a result of it. As Amir describes it, “Because history isn’t easy to overcome. Neither is religion. In the end, I was a Pashtun and he was a Hazara, I was Sunni and he was Shi’a, and nothing was ever going to change that. Nothing.” (25) As I turned the pages, I drew parallels to the other books I tackled this month, particularly, Beneath a Scarlet Sky. As racism and greed escalate into war within their countries, protagonists Amir and Pino face similar challenges to their moral character. They are both accused of treason (Amir for fleeing Afghanistan during the Russian occupation; Pino wearing a Nazi uniform instead of fighting with the Partizans or in the Italian army), and, most importantly, both characters fail to stand up for a person they love, a choice that haunts them into the future. There are also structural similarities, like the use of the childhood nemesis who returns in the end and the complicated nature of the conflicts they find themselves in, whereby there isn’t a simple right versus wrong or one side against another. Pino finds himself, even at and after the war’s end, immersed in a city of nonsensical fighting between Nazis, Fascists and Partizans, where anyone can be accused for any crime, for any conspiracy, where no one is safe, and where, when all is said and done, some of the most atrocious figures, like Nazi General Leyers, are set free to live their lives. For Amir’s part, he listens to his father’s old friend Rahim Khan describe the confusion and terror among the people once they learned of the Taliban’s true intentions but how he and others had at first embraced them after the fighting they endured under the different factions of the Northern Alliance between 1992-1996. Khan says, “When the Taliban rolled in and kicked the Alliance out of Kabul, I actually danced on that street...And, believe me, I wasn’t alone. People were celebrating at Chaman, at Deh-Mazang, greeting the Taliban in the streets, climbing their tanks and posing for pictures with them. People were so tired of the constant fighting, tired of the rockets, the gunfire, the explosions, tired of watching Gulbuddin and his cohorts firing on anything that moved. The Alliance [consisting of the factions Massoud, Rabani, and the Mujahedin] did more damage to Kabul than the Shorawi [the Russian army].” (200) People danced in the street when the Taliban rolled in? Did I read that right? Chaos and terror had reigned in WWII Italy and late 20th century Afghanistan, and above everything else, people wanted it to stop. And yet, who was to stop it? Pino’s uncle remarked in frustration in late October 1944 that “the world’s focused on France, and [has] forgotten Italy.” (289) Amir, for his part in 1989, describes a similar feeling: “That was the year that the Shorawi completed their withdrawal from Afghanistan. It should have been a time of glory for Afghans. Instead, the war raged on, this time between Afghans, the Mujahedin, against the Soviet puppet government of Najibullah, and Afghan refugees kept flocking to Pakistan. That was the year that the cold war ended, the year the Berlin Wall came down. It was the year of Tiananmen Square. In the midst of it all, Afghanistan was forgotten.” (183-4) I read these sentences and wonder, in both cases, who they wanted to help? “The world” is a big place. Who is supposed to help? And how?

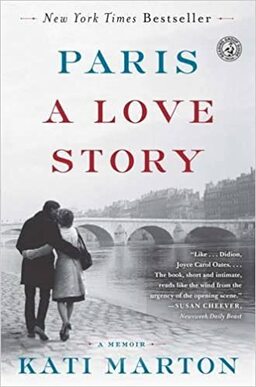

Second, Marton includes a letter she wrote to her family during her travels to Africa, while accompanying Holbrooke as newly appointed ambassador to the United Nations in 1998. During the trip they visited a refugee camp in Angola where “some of the kids have prepared a little show for us. They sing about peace and, with smiles, ask, in song, “Why so many summits, and never any change?” (137)

As the reader, I wondered, why doesn’t she answer that question? Instead she follows it with this sentence: “I am relieved to leave this battered country.” (137) Her letter is full of self-pity from the pace of the trip and her inability to stay anywhere long enough to unpack a suitcase, meanwhile she is looking real suffering in the face and not showing compassion. Perhaps it is the job of the reporter to present the facts and then let the viewer draw interpretations from the tone of the delivery. Perhaps she meant her intentions to read between the lines. She does include, however, her late husband’s views on the issues. Regarding the conflict in Bosnia, she quotes Holbrooke as saying with resolve, “At Srebrenica a month ago, people were taken into a stadium, lined up, and massacred. It was a crime against humanity of the sort that we have rarely seen in Europe, and not since the days of Himmler and Stalin. That’s simply a fact and it has to be dealt with. I’m not going to cut a deal that absolves the people responsible for this.” (131) Who is supposed to help? Reporters like Marton and diplomats like Holbrooke, sure, in order to share the facts with the world and engage leaders in conversation, and yet, Marton examines the complexity of what actually serves to change the populace. She describes a story she covered in late 1978: “the delicate process of Germans confronting their own history. Astonishingly, the country’s first mass exposure to the Holocaust came with the broadcast of an American television series of the same name.” (93-4) She reported on ABC these words, “Incredibly, this national soul-searching has been triggered by an American TV series, seen by twenty million Germans -- accomplished what scores of well-meaning documentaries have failed to do: provoked a long-overdue national debate about the past...Shock, bewilderment and surprise. Those were the immediate reactions of Germans as they watched the horrors of the Nazi rise to power...in their living rooms.” “Willem Knies, once a pilot in Hitler’s Luftwaffe, could only say he was seeing nothing he did not already know, but knowing the facts is one thing, experiencing the emotions is another. ‘It’s terrible,’ he said, ‘and it’s true.’” “Shortly after the broadcast of Holocaust,” I reported, “West German police started cracking down on bands of neo-Nazis. They’ve confiscated pictures of Adolf Hitler, swastikas, and even more chilling, an arsenal of machine guns and revolvers and explosives found in a small town near Hanover, where a group of eighteen youths had formed a neo-Nazi training camp.” (94-95, bold italics mine) I read that and wondered what influenced those youths to take up the ideals of Nazism? In the case of Hosseini’s character Assef, Amir’s childhood nemesis, Assef latches onto Hitler’s ideas in order to stoke a cultural racism against the Hazara people specific to his country Afghanistan: “...Hitler. How, there was a leader. A great leader. A man with vision...if they had let Hitler finish what he had started, the world [would] be a better place now...Afghanistan is the land of Pashtuns. It always has been, always will be. We are the true Afghans, the pure Afghans, not this Flat-Nose here [meaning Amir’s Hazara friend Hassan]. His people pollute our homeland, our watan. They dirty our blood...Afghanistan for Pashtuns, I say. That’s my vision...Too late for Hitler...But not for us.” (40) As a 13-year-old boy, Assef gifts Amir with a biography of Hitler and bullies and assaults his friend Hassan. As an adult, Assef massacres Hazara people and executes others under Sharia law. Still, this behavior doesn’t only happen in the Middle East. It isn’t specific to one group of people. Marton writes of her college days in Paris from 1967-1968, idyllic days of renewal that morphed like a nightmare during a student uprising that would come to be called Les jours de mai. She recalls that “roughly one decade after the revolution that ended my childhood [in Budapest] and forced my family to flee, I was caught up in another uprising.” (55) “Caught up in the swirl of street scuffles between students and police in Paris, I was haunted by memories of Hungarian secret police agents lynched by angry mobs, images of my family’s desperate rush to cross the Danube to sanctuary at the American Embassy, one step ahead of Soviet tanks.” (58) She recalls that “posters of Lenin, Marx, Marcuse, and Meo adorned walls stripped of the Odeon’s theater placards. Most shocking to me was a poster of Stalin. Stalin! Did these “revolutionaries” have the faintest notion of Stalin’s cruelty?” (58) Again, these are young people. Again, history repeats, with war and revolution waged by those who likely hadn’t yet been born during the last major wave of violence, which makes me wonder about the gaps in education, about the breakdown in communication between one generation to the next. How is that they, like the German pilot Willem Knies, understand the facts and yet hold none of the emotional understanding? Over the past few years, I have read only one story from the “aggressor's” point of view. While Hosseini doesn’t tell the story from the aggressor’s point of view in The Kite Runner, I have to wonder if we heard that story, whether it would sound at all like that of Bashir Khairi In The Lemon Tree, a man (a true story) whose history has been passed down orally, a history that the fighters continue to tell and retell to their children so as to keep the dream of their home alive. While the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is a completely different type of battle from that in Afghanistan, I wonder, is this how the Taliban regained control of the country so quickly this past month? From the inability of its followers to tell a new story or to gain perspective on the old one? What motivates these people? What are they trying to achieve? How can we learn more about them? Stories of takeover and oppression are as old as time. In my final book of the month, Chester Nez’s Code Talker, I learned more about Americans’ annihilation of Native Americans, and 20th century Japan’s intention to take over the world, driving home the fact that the desire to take over can be found anywhere, even at home. Of the man appointed United States Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan from January, 2009 to his death in December, 2010, Marton observed “some of [Holbrooke’s] optimism give way during those years, to an acceptance that there is such a thing as true evil in the world. How otherwise to explain neighbors and former schoolmates turning on each other with murderous rage in the heart of twentieth-century Europe? He hated cynicism, inaction, and defeatism almost as much as evil.” (133) Even with this hopeless backdrop, The Kite Runner offers two satisfying points of action by the end: a successful adoption story and its characters’ dedication to refugee efforts. After reading The Light Between Oceans and Little Fires Everywhere earlier in the month, I found it both satisfying and heartbreaking to read to the end of this story and learn of the terror and sacrifice involved in trying to rescue a child from a warzone while others opposed your efforts with doubts about how the child would be raised, when all you wanted to do was scream that the how of living surely was trumped by the need to live period, the need to give a child a chance to make it to his next birthday. Reading this story triggered a memory of when I watched Charlie Wilson’s War and how intensely sad I had been at the ending, at the lack of infrastructure put in place after the Russians were sent packing, at the lack of attention to the needs of the children left behind. Every twenty years, another generation needs to be educated. Every twenty years, another chance to try again or repeat the same mistakes. Gathering all of these stories together from where they sit in piles on my desk, I am reminded by this anonymous quote I found in Other People’s Children by Lisa Delpit, from a Holocaust survivor to a teacher: “I am a survivor of a concentration camp. My eyes saw what no person should witness: gas chambers built by learned engineers. Children poisoned by educated physicians. Infants killed by trained nurses. Women and babies shot at by high school and college graduates. So, I am suspicious of education. My request is: “Help your children become human. Your efforts must never produce learned monsters, skilled psychopaths, or educated Eichmanns. Reading, writing, and arithmetic are important only if they serve to make our children more human.” Over the past few days, I found it heartening to read of the number of countries who opened their borders to this latest wave of Afghan refugees. It is a place to start. It is a place to show love in a world so pervaded by evil. But perhaps the greater lesson here is that it is never too late to learn. Just as West Germans confronted their past via a TV show in the 1970s, I too can pick up Hosseini’s novel twenty years after my roommate blew up at my question about fighting back against the Taliban. I don’t want to be part of any blind attack or retaliation. I want to read more, to understand better, to gain a better sense of how to balance the need to hold people accountable and the need to move on with life. Stories help with this. Amazon may have 30,000 titles about WWII and 6,000 titles on Afghanistan, but there can never be too many stories. Each shares a new angle. Each sheds a little more light on the complexity of our world. Most importantly, we can work at least as hard at educating ourselves as we do at telling the world how they must live. One of the most heartbreaking points in both Amir and Pino’s stories was reading about how the people felt forgotten. Stories help us remember. Stories are our way to say we see you, and we will not forget.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|