|

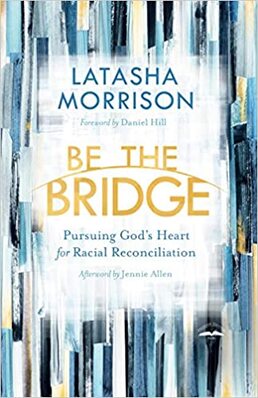

Last spring when we all entered isolation, I was fortunate enough to be a part of a women’s small group at church that was able to pivot to meeting on Zoom. As racial tensions mounted outside our walls and we talked about how to respond, one woman mentioned that she was reading Latasha Morrison’s book with white extended family members who live somewhat south of here. Herself a person of color, she expected disagreements to arise in conversation, but she was hopeful for the space to voice her societal concerns.

The copy I read was a library book, and at risk of misrepresenting Ms. Morrison, I am going to take a stab at what it’s like to revisit what sentiments and take-aways I have retained in the time between then and now. I will just admit right that the process of remembering has been a little disheartening, like I’m disappointed in my own stamina for listening and change. I found plenty to interact with in Morrison’s story as I discovered intersections with my own recent history with racial education. I realized I had much to respond to, but I didn’t know how to shape my words to be appropriate to share out loud in a group setting. I considered chalking this up to my lack of inexperience speaking about racial matters.

Part of my education recently has been learning how people of color speak more about race and have more of a racial identity at a younger age than white people. I first heard statistics on this two years ago during an event at my children’s elementary school called Courageous Conversations. So it was surprising to read that this was not Morrison’s experience. In fact, this book reminds me of Waking up White by Debby Irving which I read with my neighborhood book club in 2017, except Morrison tells a story of waking up Black -- seeking to learn the history no one offered to teach her. These books include similar examples of history that had been swept under the rug, such as the bombing of Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 which I heard Irving speak about during her talk “I’m a good person; isn’t that enough?” back in 2017. Some acts of racism are so blatant, and I appreciate this new movement to include such events in a more collective history of our country. Other situations are less clear cut and so nuanced that this is where discussion might help...or might become contentious. Like this question: Is it okay for our churches to be segregated? Of course not, right? We recall Martin Luther King Jr.’s quote about how “11 o’clock Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America” and we lament the history of whites protesting the admission of Blacks to their churches. We grieve the time when Christian slave owners debated whether they could retain rights over their slaves if they taught them the gospel and how some would decide to withhold the story of eternal salvation so to not lose their means to economic prosperity. To digress one step, in her book, Morrison addresses plantation life and how we remember it today when we tour said places. Her description took me back to my husband’s and my visit to the Hermitage back in 2018. We had skirted the long ling for the guided tour of the main house in favor of a self-guided walking tour of the slave housing and fields. It’s where we found the cotton. But while the placards within the shack dwellings provided some information of slave life, the experience on offer was a far cry from Morrison’s experience at another plantation where each visitor was asked to imagine stepping into the daily life of a particular named slave. By contrast, the majority of attention during our tour was placed on the white experience, and perhaps this is what Morrison means when she uses the word “whitewashing”: “I suspect much of the whitewashing of plantation history stems from the fact that discussing the true accounts would be shameful and might conjure feelings of ancestral guilt.” (70) I wonder if that perhaps even more often than that, the experience is white-washed simply out of habit. Perhaps these are the narratives tourists expect when they come to visit. And yet, I bristle when Morrison makes an almost parallel assertion regarding church attendance, “You don’t see many White people attending churches of color or ethnically diverse churches as bridge builders. Why? Maybe it’s because seeking ethnically diverse churches would highlight their complicity in structures of racism, and that complicity would bring so much shame and guilt.” (77) Goodness! I wished I could talk with her right on that page because if I felt any complicity in this situation, I would need someone to point it out to me! I didn’t think I fell into her category, and I wondered how many people she knew would identify with that, and what that even looked like. For myself, I remember that when I first moved to Cambridge and walked my new neighborhood, I was disappointed that the closest, most convenient church I found was Korean. I assumed I wouldn’t be welcome there. I don’t speak Korean, and I wouldn’t want the members there to have to go out of their way to make me feel comfortable. I remember really wanting a church home, but I didn’t want to impose or enter a situation where I might feel out of place either. Nowadays, in contrast, I have thought about how it would be interesting to attend the Ethiopian church where my son’s friend’s family goes. And yet, I haven’t. I still assume I’m not wanted, like these groups need to preserve a safe space for themselves. Just a few pages earlier in her book, for example, Morrison herself admitted to a time when she sought out the black table in the cafeteria in high school after a painful experience where her fellow classmates rejected her proposal to celebrate Black history month. She states: “I wasn’t complaining about the separation. I needed a place to vent, to voice my anger. I needed a place of solidarity and safety.” (65) I agree that there are times when you want the support of those familiar with your experience. I prefer to ask close friends for advice, just as I prefer to speak about my spiritual life in women’s groups instead of co-ed ones. On the other hand, I’m glad I go to a fairly diverse church, one that, I only found out after years of attendance, was founded by a group of Korean Christians who wanted to create a space that was welcoming for all people. The result of this natural mixing is that now when I visit all-white churches I feel uncomfortable, like there are people missing. I have to wonder if something about the culture of those churches is repelling people of color. And now, as I type this, I remember a close friend from junior high. She was the first close friend I had with whom I talked in depth about God on a regular basis. She and I used to exchange notes with Bible verses on them. She and I sat at the same lunch table nearly every day before she moved away after graduation. The thing is, my friend was Korean, and at the time, I had no idea that over a decade would pass before I had another Korean Christian friend. At the time, I only knew the longing that comes with separation from an old friend. I wonder if this is the longing Morrison felt when she created Be the Bridge and went on to write her book. Sharing life is possible. Patient listening is possible. Our selfish motives and insecurities might get in the way, but with grace, perhaps we can begin to construct a new understanding. If we are able to make deliberate effort to step outside of the comfort zone of our own groups, eventually perhaps it may even feel natural to sit at the same lunch table once again.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author's Log

Here you will find a catalog of my writing and reflections. Archives

December 2022

|